Credit: Artwork: Created with OpenAI DALL·E (via ChatGPT)

Background

Synopsis: Although water vapor (forming clouds) is by far the most abundant greenhouse gas and carbon dioxide gets most of the attention, other greenhouse gases like methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases are far more powerful. Learning where they come from and how to reduce them is key to slowing atmospheric warming.

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) gets a lot of attention. It’s the subject of books and podcasts, the cause of climate protests, the focus of international summits. It has become the face of climate change.

- Greenhouse gases trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere.

- Although water vapor (forming clouds) is by far the most abundant greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide is the most well-known.

- These gases absorb heat and then release some of it back toward the planet’s surface, keeping Earth warm enough to support life. Without them, Earth would be a frozen world, with average surface temperatures barely above freezing.

- Among these gases, carbon dioxide plays a leading role. It’s the most important long-lived greenhouse gas, meaning it stays in the atmosphere for a long time and accumulates.

- CO2 levels have naturally fluctuated throughout Earth’s history. Warming releases CO2 and cooling traps CO2.

- But today, rather than naturally lagging a warming event, CO2 levels are increasing.

- Burning hydrocarbons like coal, oil, and natural gas releases carbon that had been locked in the subsurface for millions of years. This combustion puts extra CO2 into the atmosphere, carbon that was once part of long-term geological storage.

- Higher CO2 in the atmosphere also means more CO2 gets absorbed by the ocean. This makes seawater more acidic, potentially affecting marine life and coral reefs.

- Even though carbon dioxide isn’t the most powerful heat-trapping greenhouse gas molecule for molecule, it’s the second most abundant, behind water vapor. That makes it the standard against which others are measured.

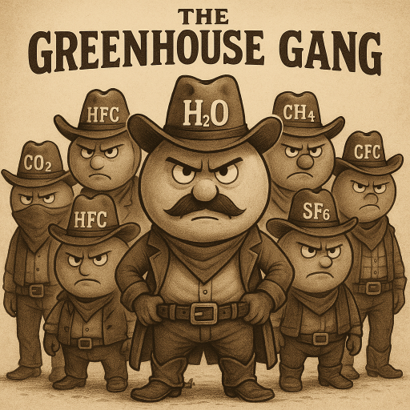

- Scientists use a metric called Global Warming Potential (GWP) to compare how much heat different gases trap over a set period of time, usually 20 or 100 years.

- These comparisons are reported in CO2 equivalents (CO2e), a way to translate the warming effect of other gases into units we already understand.

- But carbon dioxide doesn’t act alone. It may be the most common and familiar greenhouse gas, but it’s just one member of a larger gang, some of which are far more potent.

- The other gases operate in the background, often in smaller quantities, but with outsized effects on Earth’s temperature. From agriculture to industry to refrigeration, they slip into the atmosphere naturally and through everyday human activity.

- To understand the full story of climate change, we need to get to know the rest of the gang as well.

- Even though methane (CH4) stays in the atmosphere a much shorter time than CO2, it is more powerful as a heat trapping gas, especially over a couple of decades.

- It is released naturally by wetlands, termites, and geological seeps.

- Human-related emissions stem from leaks and venting during oil and gas extraction, livestock digestion and manure, landfills, and flooded rice paddies.

- Methane molecules remain in the atmosphere for about 10 to 20 years. Over 20 years, methane is about 80 times more powerful than CO2; over 100 years, it’s about 30 times more powerful.

- Methane is difficult to track due to its many small, scattered sources, yet atmospheric concentrations have been rising steadily for decades.

- Plugging leaks in oil and gas systems, capturing emissions from landfills and manure, and improving livestock and rice farming practices could help to reduce methane’s growing impact.

Credit: By Photo by Scott Bauer (US Department of Agriculture) Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6554285

- Nitrous oxide (N2O) is often overlooked, but it is a powerful and long-lasting greenhouse gas with nearly 300 times the warming potential of CO2 over a 100-year period.

- Natural sources, including soils under native vegetation and oceans, account for about 62% of total emissions.

- Human activities, primarily agriculture, hydrocarbon combustion, and industrial processes, are responsible for the remaining 38 percent.

- The largest human-related source is agriculture, particularly the use of synthetic fertilizers and manure which add excess nitrogen to soils and accelerate microbial processes that release N2O. Smaller contributions come from biomass burning, atmospheric deposition, and human wastewater.

- Nitrous oxide remains in the atmosphere for about 110 years and atmospheric concentrations have been rising steadily, mostly due to the increasing global use of nitrogen-based fertilizers.

- Reducing N2O emissions involves using fertilizers more efficiently, applying slow-release or organic alternatives, adopting precision agricultural techniques, and improving livestock waste management.

- Fluorinated gases are synthetic compounds used in refrigeration, electronics, fumigation, and industrial applications. Though released in smaller amounts than CO2 or methane, they are among the most potent and long-lasting greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

- These gases do not occur naturally. They are created for specific uses such as cooling systems, semiconductor manufacturing, fire suppression, and pest control.

- Once released, fluorinated gases are remarkably stable. Some remain in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, trapping heat far more effectively than CO2.

- Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) is the most powerful greenhouse gas known, with a global warming potential over 25,000 and a lifetime of 3,200 years. It is used as an insulator in electrical systems, but safer alternatives exist.

- Trifluoromethane (HFC-23) and hexafluoroethane are widely used in electronics and refrigeration. Both have GWP’s of over 12,000, and one molecule of hexafluoroethane can persist for up to 10,000 years.

- While some of these gases are regulated or phased out, others are still in use and their concentrations are slowly increasing. Even in tiny amounts, their long lifespans and high warming potentials make them important to monitor and manage.

Credit: By Kreuzschnabel - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42269777

- Each of these gases contributes to warming in different ways, but all offer opportunities for reduction. The strategies vary by gas, depending on their sources and uses.

- Methane

- Agriculture is the largest source of human released methane

- In agriculture, methane from cows can be changed by changing their diets. One feed additive, Bovair, has cut emissions by up to 30%.

- Rice farming can lower methane output by adjusting water levels, though care is needed to avoid increasing other emissions like nitrous oxide.

- Fixing leaks in oil and gas systems is one of the most effective ways to cut methane emissions. Most leaks can be fixed at little cost to companies, and doing so means more gas to sell. Methane emissions could be reduced tenfold by addressing leaks, venting, and flaring across oil and gas operations.

- MethaneSAT, a new satellite, tracks methane from space. It collects high-quality, global data to show where methane is coming from, how much is being released, and how that’s changing over time.

- Nitrous Oxide

- Nitrous oxide emissions can be reduced with the utilization of precision agricultural tools such as GPS-guided equipment and remote sensing to help farmers apply just the right amount of fertilizer, reducing waste and emissions.

- New types of fertilizers, like slow-release formulas and additives that control how nitrogen breaks down in the soil, help prevent nitrogen from washing away and reduce nitrous oxide emissions.

- In addition, researchers are developing tools that can continuously monitor nitrous oxide emissions from soil in real time. By combining detailed monitoring with improved nutrient management, farms can reduce nitrous oxide emissions while maintaining healthy crop yields.

- Most industrial N2O emissions come from the production of synthetic fertilizers and nylon. These processes generate large amounts of nitrous oxide as a byproduct. Installing emissions controls at these facilities can nearly eliminate N2O output and many countries have already done so. However, some plants in the U.S. and China still lack these upgrades, making them major remaining source.

Credit: By Lynn Betts - U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Photo no. NRCSIA99241, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6303636

- Fluorinated Gases

- Emissions of fluorinated gases used as refrigerants can be reduced by fixing leaks, handling them more carefully, and switching to newer refrigerants that trap less heat.

- In industries, like aluminum, magnesium, and semiconductor manufacturing, companies can cut emissions by capturing and destroying the gases before they escape, and by switching to cleaner alternatives.

- In the electric power industry, sulfur hexafluoride is used to insulate equipment and prevent arcing. Its emissions can be reduced by repairing leaks, recycling the gas, or using equipment that doesn’t require SF6 at all.

- Cars and truck also release fluorinated gases through air conditioning systems. Using better parts and switching to low-impact refrigerants can reduce these emissions.

- Under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol and the U.S. AIM Act, production and use of high-GWP hydrofluorocarbons are being phased down, with EPA incentives for reclaiming and destroying existing supplies.

Credit: NOAA, https://gml.noaa.gov/aggi/aggi.fig2.png

- Carbon dioxide may get the most attention, but it’s not acting alone. Other greenhouse gases like methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases are powerful players in the warming of our planet.

- Understanding this full “greenhouse gang” gives scientists better tools to track emissions, helps policymakers design smarter strategies, and show individuals where their choices can make a difference.

- By looking beyond carbon, we’re not just identifying new problems; rather, we’re finding faster, smarter ways to reduce heat-trapping emissions and protect Earth’s future.

Episode script

Greenhouse gases trap heat in the atmosphere and keep Earth warm. Without them it would be a frozen iceball – as it once was before.

There are many greenhouse gases. Water vapor is by far the largest by volume, and does most of the warming.

Carbon dioxide is the weakest greenhouse gas in warming potential, but the second most abundant.

Carbon is always moving between Earth and sky in what’s called the carbon cycle.

But since humans have industrialized, we’re transferring carbon that was held in fossil fuels into the atmosphere, where it lasts about a century.

We measure the warming impact of other gases in CO2 equivalent.

Methane, for instance, is 80 times more potent than CO2, but lasts in the atmosphere only a few decades.

It’s naturally produced by decaying plants in swamps, lakebeds, and forest floors. And by human sources like natural gas leaks and livestock.

Nitrous oxides also occur naturally, emitted from soils beneath wild plants and oceans. And through our agriculture, by using nitrogen-based fertilizers.

These are 300 times more potent than CO2, though produced in much smaller quantities.

Fluorinated gases are manmade, and emitted only from human sources, like leaking refrigerant.

The volume is tiny, but they’re thousands of times more potent than CO2, and endure for thousands of years.

Only by understanding the mix and potency of greenhouse gases can we understand how to best manage them.