Credit: National Park Service, public domain

Big Bend is one of the largest, most remote and least visited national parks in the U.S.

It’s a land of great diversity. More than a mile of elevation change. More than 100 degrees Fahrenheit of temperature fluctuation annually.

Diverse topography—deserts, mountains, canyons, rivers and springs—with different life in each ecozone.

And because of that, more ecological diversity than any other national park: more species of birds, butterflies, bats, reptiles, ants and plants. And the largest age range of fossils, too, because of its complex geologic history.

It also has a long and varied human history.

Just after the last Ice Age, 11,000 years ago, nomadic hunters frequented the area. Tribes settled in Big Bend 7,500 years ago. Spanish explorers built forts in the area 500 years ago. Two-hundred years ago, the Apache then the Comanche displaced the indigenous Chisos tribe.

The area became a stop on the Comanche Trail as they migrated from buffalo-hunting grounds in the Texas Panhandle to raid Spanish missions in Mexico.

Big Bend became part of Texas when it became a republic, in 1836. Texas made it a state park a hundred years later, then donated it to the U.S. government.

Since 1944, Big Bend has been part of the National Park Service—and this 80th anniversary would be a great time to visit!

Background

Synopsis: They say everything is bigger in Texas, and that includes Big Bend National Park! With its rich human history and remarkable natural gifts, this vast land of dramatic contrasts was dedicated as a national park 80 years ago, on June 12, 1944. It took nine years after the legislation passed the U.S. Congress in 1935, in an era of economic depression and war, for the State of Texas to acquire the land and then give it to the national government for the purpose of a national park. Texans, appropriately, like to call Big Bend “Texas’ Gift to the Nation.”

- The name “Big Bend” comes from the northeastward bend in the Rio Grande River between two long southeastward-flowing reaches. The “Big Bend region” is the southern part of the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas, along its border with Mexico.

- While the region has sparse population densities of just 1 to 2 residents per square mile, more than 17% of the land (1.2 million acres [5,000 km2]) has been set aside for public use on the American side of the border.

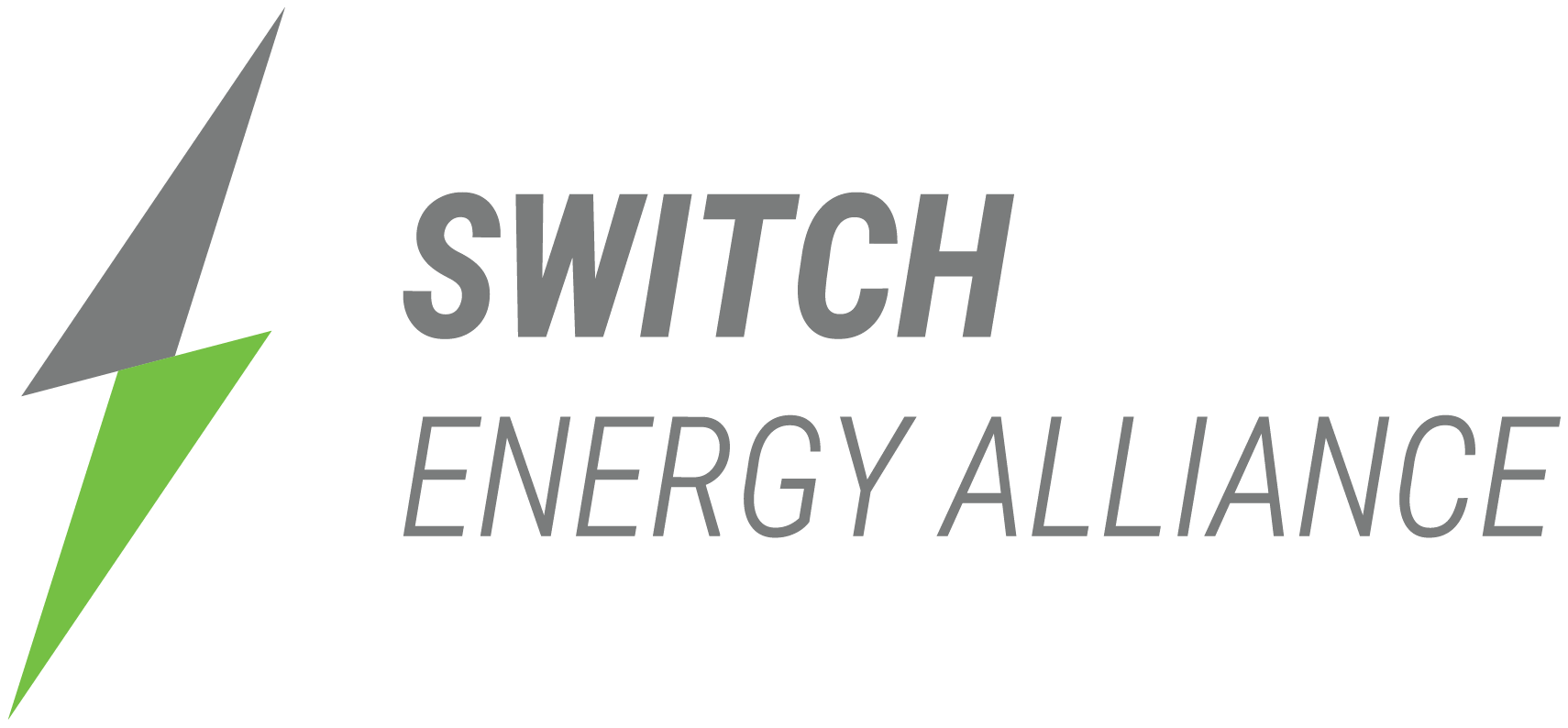

Official National Park Service map of Big Bend National Park.

Credit: National Park Service - About two-thirds of this public land is Big Bend National Park (801,163 acres [3,242 km2]), with the rest in Big Bend Ranch State Park, Chinati Mountains State Natural Area, and Black Gap Wildlife Management Area.

- Big Bend National Park by itself makes up more than 20% of the publicly accessible land in Texas.

- All the other national and state park areas in Texas together would fit inside Big Bend National Park.

- While the region has sparse population densities of just 1 to 2 residents per square mile, more than 17% of the land (1.2 million acres [5,000 km2]) has been set aside for public use on the American side of the border.

- Big Bend National Park is a land of both contrasts and scale.

- Vertical relief in the park is more than a mile at 5,975 ft (1,821 m) from the lowest place in the park at 1,850 ft (564 m) above sea level (near Rio Grande Village) and the highest point at 7,825 ft (2,385 m) (on Emory Peak).

At 7,325 ft (2,233 m), Casa Grande is not Big Bend National Park’s tallest peak, but this flat-topped rhyolitic mountain greets hikers in the Chisos Basin and might be the most distinctive peak, with its sheer cliffs making it look something like a birthday cake!

Credit: Juli Hennings, Bureau of Economic Geology - Temperatures can be 10°F to 20°F (5–11°C) warmer in the desert than in the Chisos Mountains.

- Biomes in the park include desert to semi-desert grassland, desert scrub and woodlands, montane chaparral and montane woodlands, such as the Chisos sky island that includes boreal species normally found at northern latitudes.

- With its great diversity of ecosystems, Big Bend is the most ecologically diverse of all the U.S. national parks, with the most species of birds, butterflies, bats, reptiles, ants and plants.

Big Bend National Park supports significant biological diversity, thanks to its range in elevation. Fifty-six species of reptiles, 75 species of mammals, more than 450 species of birds and more than 1,200 species of plants have been documented at the park, including a specific variety of tall, very deep blue “Big Bend bluebonnets,” Lupinus havardii.

Credit: National Park Service, public domain - Big Bend has the widest range of fossil ages of all American national parks. Fossils in the park have ages that range over more than 450 million years, from tiny Ordovician conodonts; to mollusks, dinosaurs and pterodactyls of the Mesozoic; to crocodiles and mammals of the Cenozoic.

The Fossil Discovery Exhibit tells some of Big Bend’s most intriguing fossil stories. With $1.5 million dollars of funding by the Big Bend Conservancy, the open-air museum opened in January of 2017.

Credit: Big Bend Conservancy - We talked about the amazing and complex geological story of Big Bend National Park in ED-371 Rio Grande’s Big Bend.

- Vertical relief in the park is more than a mile at 5,975 ft (1,821 m) from the lowest place in the park at 1,850 ft (564 m) above sea level (near Rio Grande Village) and the highest point at 7,825 ft (2,385 m) (on Emory Peak).

- Big Bend has a rich human history that began at least 11,500 years ago, just after the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, when hunter-gatherers were living in the region.

- Initially, nomadic bands hunted large game as their source of material for clothing, shelter and food but transitioned to relying more on plant material, maintaining a sustainable lifestyle for 7,500 years.

- Starting around AD 1000, the indigenous Chisos People in the region shifted to practice agriculture, pottery and trading.

- Around 1519, Spanish mission priests arrived, then Spanish explorers arrived around 1535 in search of gold, silver and Indigenous people to enslave.

- By the 1700s, the Chisos People of the Big Bend region were replaced by the Mescalero Apache Tribe, who were then forced out by the Comanche Nation.&

- By the 1750s, the Spanish were dividing the land up into cattle ranching tracts and building forts called presidios to help protect the ranches.

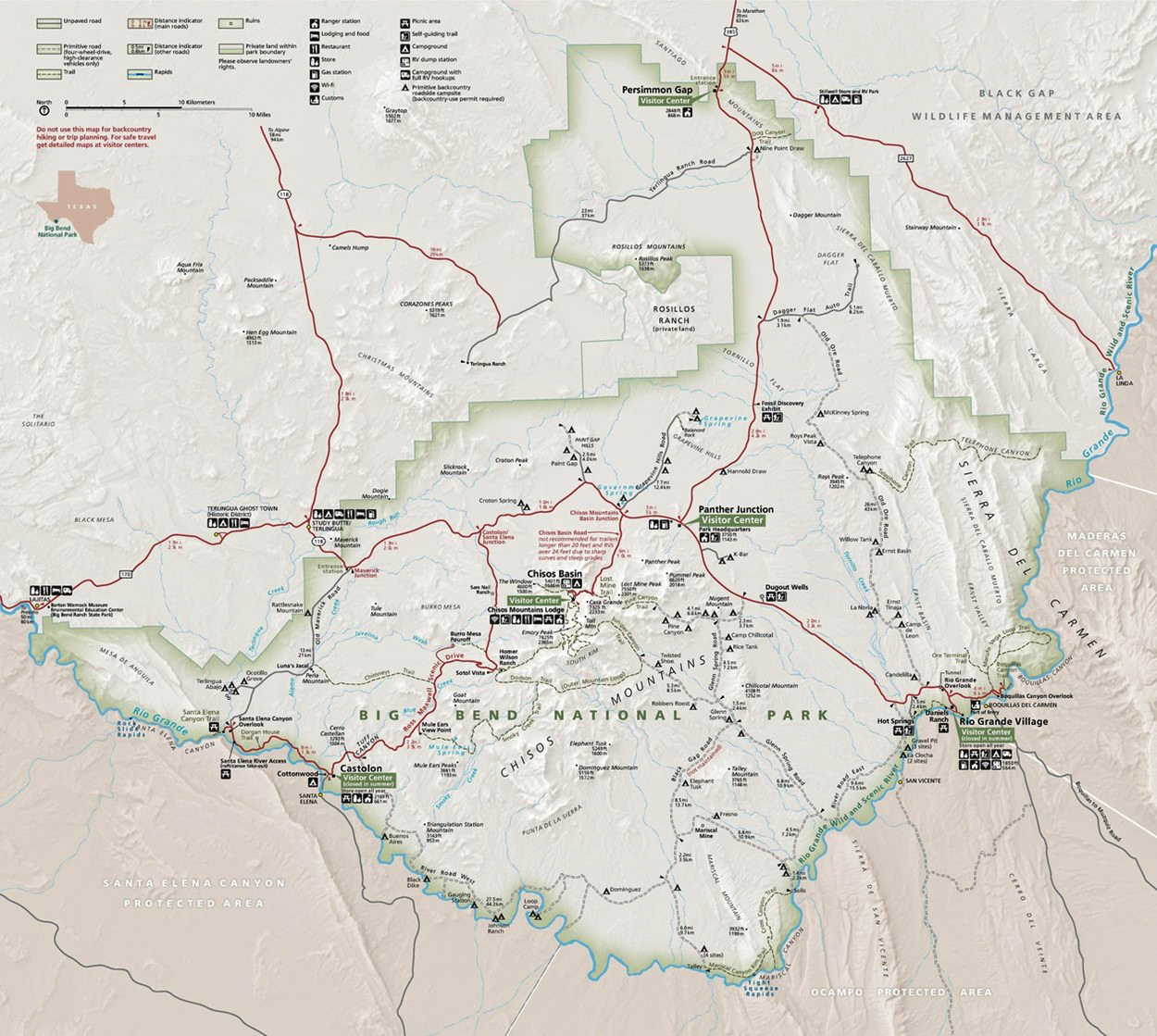

- In the early 1800s, nomadic Comanche bands rode south to raid the Spanish missions and forts south of the Rio Grande. These regular autumn expeditions were known as the “Comanche Moon” season and created a major thoroughfare known as the Comanche Trail. In places it was trampled a mile wide.

The Comanche Trail was a network of parallel and branching trails, always following sources of good water, that ran from Comanche summer buffalo-hunting grounds in what is now Kansas, Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle to crossing points along the Rio Grande River and beyond into what was called New Spain, in northern Mexico. This map shows crossing points at Lajitas and Paso de Chisos (near the present border between the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Coahuila), but other crossing points ranged from what is now Presidio–Ojinaga to Boquillas.

Credit: National Park Service, public domain - In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, and in 1836, Texas declared its independence from Mexico. After 1848, the border between Mexico and the United States was defined as the Rio Grande River in the Big Bend region.

- During the 1880s, many American ranchers flocked to Big Bend. In combination with use by Mexican ranchers and drought, the land was soon overgrazed.

- Mercury (also known as quicksilver) mining replaced ranching as the primary economic driver of the region in the 1890s. Mining of mercury continued until 1943.

- In 1899, Robert T. Hill led the first geological expedition of the Big Bend region with six men in three boats. It took nearly a month in the rugged terrain.

- With a view to preserving the region’s stark, natural beauty, the State of Texas created Texas Canyons State Park in May of 1933, building roads and facilities with the help of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) through 1942.

- After the stock market crash of 1929, many Americans found themselves having to wait in soup lines to eat. Franklin Delano Roosevelt (also known by the initialism FDR) was elected president of the United States by a landslide in 1932. In 1933, President Roosevelt’s administration created the CCC program as part of its “New Deal” series of economic policies. The CCC provided training and employment for more than 3 million young men from needy families as they built infrastructure to support the conservation of natural resources at 4,500 camps throughout the nation.

- The CCC got to work, 85 mi (137 km) from the nearest West Texas town, with 200 young men who used picks, shovels and rakes to build a 7-mi-long (11 km) all-weather road into a topographic depression in the heart of the Chisos Mountains known as the Chisos Basin. They moved 10,000 truckloads of material, built 17 culverts that are still in use today, constructed a camp and established a water supply.

Civilian Conservation Corps work crew constructing the road in Green Gulch that leads into the Chisos Basin during the mid-1930s.

Credit: National Park Service, public domain - The park was renamed Big Bend State Park, and in 1935, the U.S. Congress, led by Texans believing the Big Bend area to be equally worthy of national protection and attention as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, passed legislation to establish it as a national park.

- Starting in 1940, the CCC added a store and four stone cottages, surveyed the park boundaries, and built hiking trails that are still used today.

- Texas acquired the land for the park in 1942, but the CCC camp closed down in that year because of American entry into World War II.

- President Roosevelt, on behalf of the people of the United States, personally accepted the deed for the park from Texas businessman Amon Carter, representing the State of Texas, on June 6, 1944—also known as the famous “D-Day” of World War II.

Amon Carter (right) presented the deed to Big Bend National Park to President Roosevelt on June 6, 1944, the morning of “D-Day,” the Allied landings at Normandy, France.

Credit: National Park Service, public domain- Six days later, on June 12, 1944, Big Bend National Park was officially established.

- President Roosevelt felt like the nation deserved some good news that week.

- In the late 1970s, the National Park Service, after extensive studies and public involvement, recommended that about 2/3 of the area of the park (as it existed then) be permanently protected as a component of the National Wilderness Preservation System, which would also require an act of Congress. These areas were then, as today, undeveloped, and wilderness designation would keep them that way while not impacting any of the recreational activities of the public in the park. Congress never acted.

- In the 1980s, Big Bend National Park grew with the addition of 57,000 acres (230 km2) in the North Rosillos Mountains thanks to The Nature Conservancy, and it really did take an act of Congress. Several years later, the National Park Service purchased another 10,000 acres (40 km2) there for a total addition of 67,000 acres (271 km2).

- In 2023, the Big Bend Conservancy acquired another parcel of land along Terlingua Creek near the northwestern boundary of the park with the goal of adding it to Big Bend National Park as soon as Congress acts again. The Big Bend Conservancy has also created educational exhibits like the Fossil Discovery Exhibit open-air museum over the years.

- A citizens’ group, Keep Big Bend Wild, in cooperation with the National Park Service, has resurrected the goal of protecting the park as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System, which arguably is more important than ever as the park becomes better known and visitation increases. It will still require congressional action.

- Big Bend National Park is part of an even larger international system of protected areas known as the El Carmen Big Bend Complex.

- From the earliest days of planning for the national park, international conservation was considered. In 1944, President Roosevelt, in cooperation with Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho, laid out a grand vision that the future binational protected El Carmen Big Bend Complex would include at least 14% of the border between the two countries. But tragedies struck, and these plans were set aside (we will tell that story in a future EarthDate episode).

- Mexico, the United States, and Texas have made great progress protecting significant lands along the border as a “trans-frontier conservation area” of more than 3 million acres (12,200 km2). The area includes Big Bend National Park, Big Bend Ranch State Park, Black Gap Wildlife Management Area, Rio Grande Wild & Scenic River and protected areas on the Mexican side of the border including Maderas del Carmen, Ocampo, Cañón de Santa Elena and Monumento Natural Río Bravo del Norte.

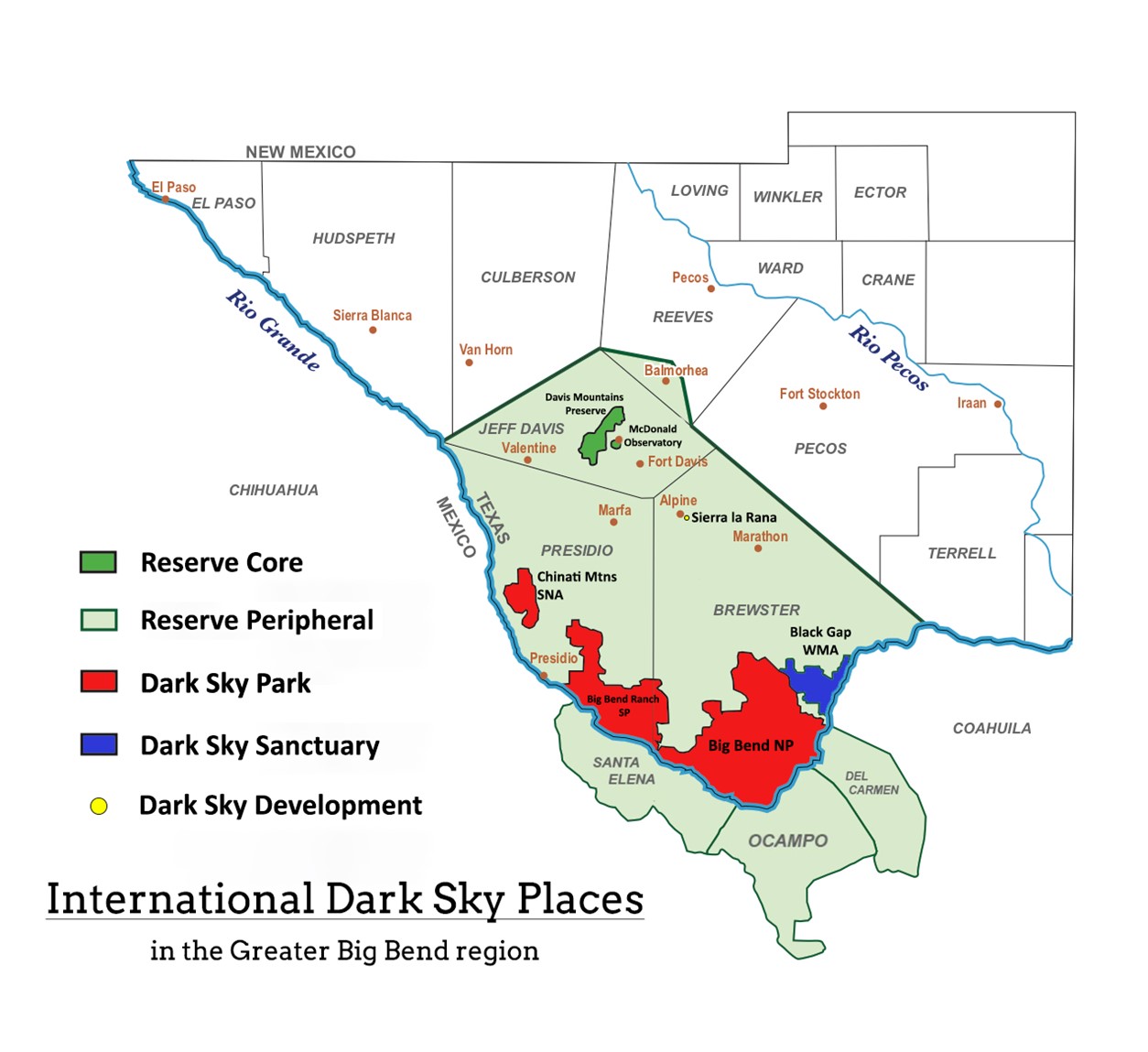

- The Greater Big Bend International Dark Sky Reserve covers more than 9 million acres (~36,400 km2), making it the world’s largest designated Dark Sky Place.

The Greater Big Bend International Dark Sky Reserve covers more than 9 million acres and is the world’s largest protected Dark Sky Place. It includes three Dark Sky Parks, three Mexican protected areas, a Dark Sky Sanctuary, and a Core Reserve around the Davis Mountains where the University of Texas McDonald Observatory is located. Protected areas on the south side of the Rio Grande River include the Cañón de Santa Elena Flora and Fauna Protection Area, the Ocampo Flora and Fauna Protection Area, and the Maderas del Carmen Flora and Fauna Protection Area.

Credit: University of Texas McDonald Observatory