Credit: Andreas Trepte (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Even if you’ve watched documentaries about honeybees, you may know little of their remarkable life within the hive.

A queen will lay a million eggs in her 5-year lifetime, which she places in wax brood cells.

Fertilized eggs grow into sterile female workers. Unfertilized eggs become male drones.

When the queen gets old, nurse bees bathe regular female larvae in royal jelly, which turns them into queen larvae. The queen that emerges first will kill the other larvae to become sole heir to the throne.

Her first duty is to fly away and mate with up to a dozen drones, to ensure genetic diversity. She’ll store their sperm in her abdomen for the rest of her life, to fertilize eggs.

When she returns to the hive, she takes the place of the old queen.

Worker bees go through an apprenticeship of sorts. Their first job is to clean the nursery. Once they develop the glands that produce royal jelly, they become nurse bees, feeding and caring for larvae. When they develop wax glands, they become engineers, building and repairing the hive.

Finally, they graduate to gathering nectar, and that’s when the work really begins.

A field bee never sleeps and will work herself to death flying hundreds of miles in a thousand trips to and from the hive, carrying the precious cargo that will sustain the colony.

We’ll have more on the fascinating process of how bees make honey—and how essential they are to our lives—on future EarthDates.

Background

Synopsis: World Honeybee Day is observed on the third Saturday of August, so let’s honor these amazing insects throughout August with a few EarthDate episodes. Honeybees have been around for more than 20 million years, when they first took a “sweet” vegetarian evolutionary path away from their carnivorous cousins. This shift in food source required the development of a strict communal organization, resulting in large hives that operate like a single large organism.

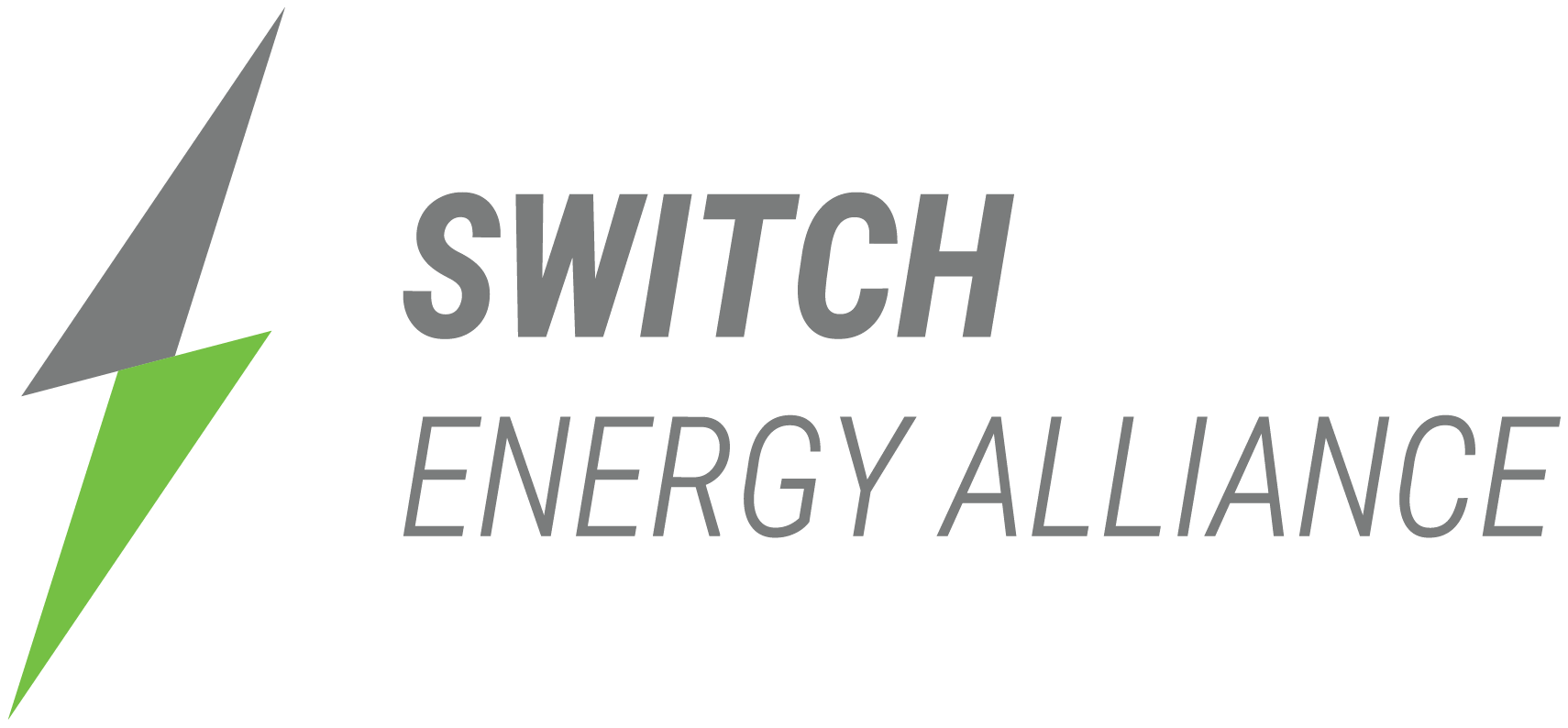

Credit: George Poinar Jr. (OSU College of Science)

- Honeybees belong to the genus Apis of the Hymenoptera order of membrane-winged insects, along with other species of bees, wasps, ants, and sawflies.

- Bees are believed to have coevolved as pollinators to flowering plants during the Cretaceous Period. The oldest-known fossil bee is about 100 million years old and was found in Myanmar. It looks like a cross between a modern bee and a wasp.

- Most of the thousands of species of bees alive today are solitary, excavating tunnels where they lay their eggs, but honeybees are social insects ruled by a single fertile queen.

- Researchers think that honeybees evolved from carnivorous ancestors that turned vegetarian after acquiring a taste for nectar.

- The oldest fossil honeybee is more than 22 million years old and was found in Lower Miocene rocks of Western Germany.

- As Pleistocene ice melted about 14,000 years ago, huge forests took root in the former tundra, and pollinators flourished, expanding their range dramatically as the ice retreated.

- Today, honeybees can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

- Honeybees nest in large communities called hives, which are made up of 20,000–60,000 bees. There are three types of bees in a hive: the queen, the drones, and the workers.

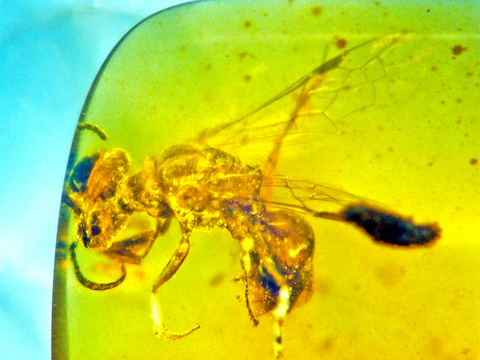

Credit: Jessica Lawrence, Eurofins Agroscience Services (CC BY 3.0)

- The queen is the largest of the bees, and there is only one queen per hive.

- She may lay 1 million eggs in her 3- to 5-year lifetime and can lay nearly her body weight in eggs every day—up to 2,500 eggs per day in the summer. She is the only bee that lays eggs in the hive, and she requires attendants to feed and groom her while she works.

- She also regulates behavior and activity in the hive by releasing pheromones.

- When the old queen stops producing as many eggs, a new queen is needed. Nurse workers select several female larvae and feed them an exclusive diet of royal jelly—actually bathing them in it—which causes their ovaries to develop. If the queen dies and an emergency queen is needed, workers can create a few queen larvae with fertilized eggs that are less than five days old. The first new queen to emerge kills the other royal larvae.

- Just 5–12 days after she emerges, the new queen files out of the hive to mate with 12 or more drones from nearby colonies, to ensure genetic diversity in her own colony. During this flight, she stores enough sperm in her abdomen to fertilize eggs for the rest of her life. If she doesn’t mate within 20 days, she loses the ability to produce eggs.

- The old queen will take a small swarm along to support her and leave the hive before the new queen returns from mating.

- Two days after mating, a new queen can start laying eggs. She lays two different types of eggs. Fertilized eggs develop into sterile female worker bees (unless chosen to be new queens) and carry both male and female genes. Unfertilized eggs become male drones and carry only the queen’s genes.

- Drones are male bees whose sole job is to fertilize a new queen if needed, then they die.

- A healthy hive will have the luxury of a couple hundred drones at a time to ensure the survival of the colony—usually less than 1% of the population.

- Drones can’t protect the hive because they lack stingers, and they don’t have the equipment necessary to collect nectar or pollen. They don’t even have the ability to feed themselves, so worker bees have to place food on their tongues so they can eat.

- As winter approaches or if food is scarce, drones are chased away from the hive to starve.

- Worker bees carry out the everyday business of the hive and progress through a series of jobs that support the community as they mature.

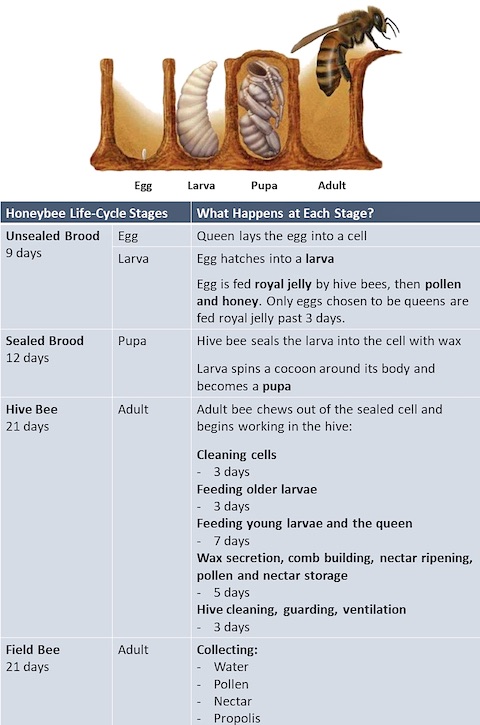

Credit: USDA, Nottingham Bees

- It takes 3 weeks for honeybees to grow from an egg to an adult, then they spend about 3 weeks working inside the hive.

- After emerging from their brood cells, the first job of young adults is to help clean the nursery.

- Then they may become nurse bees, developing hypopharyngeal glands that produce the royal jelly that is fed to the hive’s larvae. Regular larvae are fed royal jelly for only 3 days, but future queens are given royal jelly for about 3 weeks.

- The young adults may also help ripen nectar into honey and seal it into storage cells or help maintain a constant internal temperature (around 93°F or 34°C) in the hive by fanning water droplets while clustering. This evolution to cluster enables honeybees to survive in multiple different climates.

- Once adult bees develop abdominal wax glands, they may go to work as engineers, secreting and chewing wax to strengthen it and molding it into new hexagonal honeycomb cells to renovate the hive.

- They may graduate to other jobs like attending the queen, guarding the hive, or being undertakers. Most bees will leave the hive to avoid contaminating it if they are sick or dying, but in the event they die in the hive, undertaker bees keep the hive fastidiously clean by removing the bodies.

- The adults also start to learn about the area near the hive by taking orientation flights.

- After their time as a “hive bee,” they are promoted to “field bee.” They literally work themselves to death at this job, lasting as little as just 3 weeks in the busy summer, and as many as 5 additional months in the winter.

- Honeybees have six legs and four wings. During flight, the front pair of wings attaches to the back pair of wings via a row of hooks on the leading edge of the back wings, like a tiny strip of Velcro.

- Honeybees flap their wings 12,000–15,000 times per minute to stay aloft—nearly twice as fast as hummingbirds. They can fly as fast as 20 mi (32 km) per hour but usually cruise at around 12 mi (19 km) per hour. They can fly 6 mi (10 km) nonstop.

- Their tiny brains are no bigger than a sesame seed, but they are able to locate and evaluate sources of food and communicate quality, direction, and distance to other foragers using a complex waggle dance made up of buzzes and pheromones. Unlike hummingbirds, honeybees cannot see the color red, but they can still find red flowers.

- Worker bees are the only bees that can sting mammals, but they do so only as a last resort. Their stinger is attached to their internal organs, and they cannot pull the stinger out of an enemy, so when their stinger rips off, they die. If a bee lands on you, blow it off instead of hitting it. If you are stung, immediately scrape off the singer and venom pump with a fingernail—don’t squeeze the stinger, which will inject more venom. The venom causes a burning sensation, and some human are severely allergic to it.

- Honeybees never sleep; they are “busy as bees” for their entire lifetimes.

- The third Saturday in August is World Honeybee Day, celebrating both honeybees and beekeepers. Originally designated National Honeybee Day in the United States in 2009, it is now celebrated globally.

- Honeybee hives are social communities in which every member has a defined role, but that is not the end of the story. The next few EarthDate episodes will address the special properties of honey and how bees produce it, the role of honeybees as pollinators, and the dangers bees face from pests and pesticides.