Credit: WFan, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Background

Synopsis: Mummies have long fascinated us with their appearance, but now researchers are uncovering what they may have smelled like. Using advanced chemical techniques, scientists are identifying the ingredients ancient Egyptians used in embalming and even recreating those scents. The science of smell is offering a new way to understand ancient rituals and preserve the past.

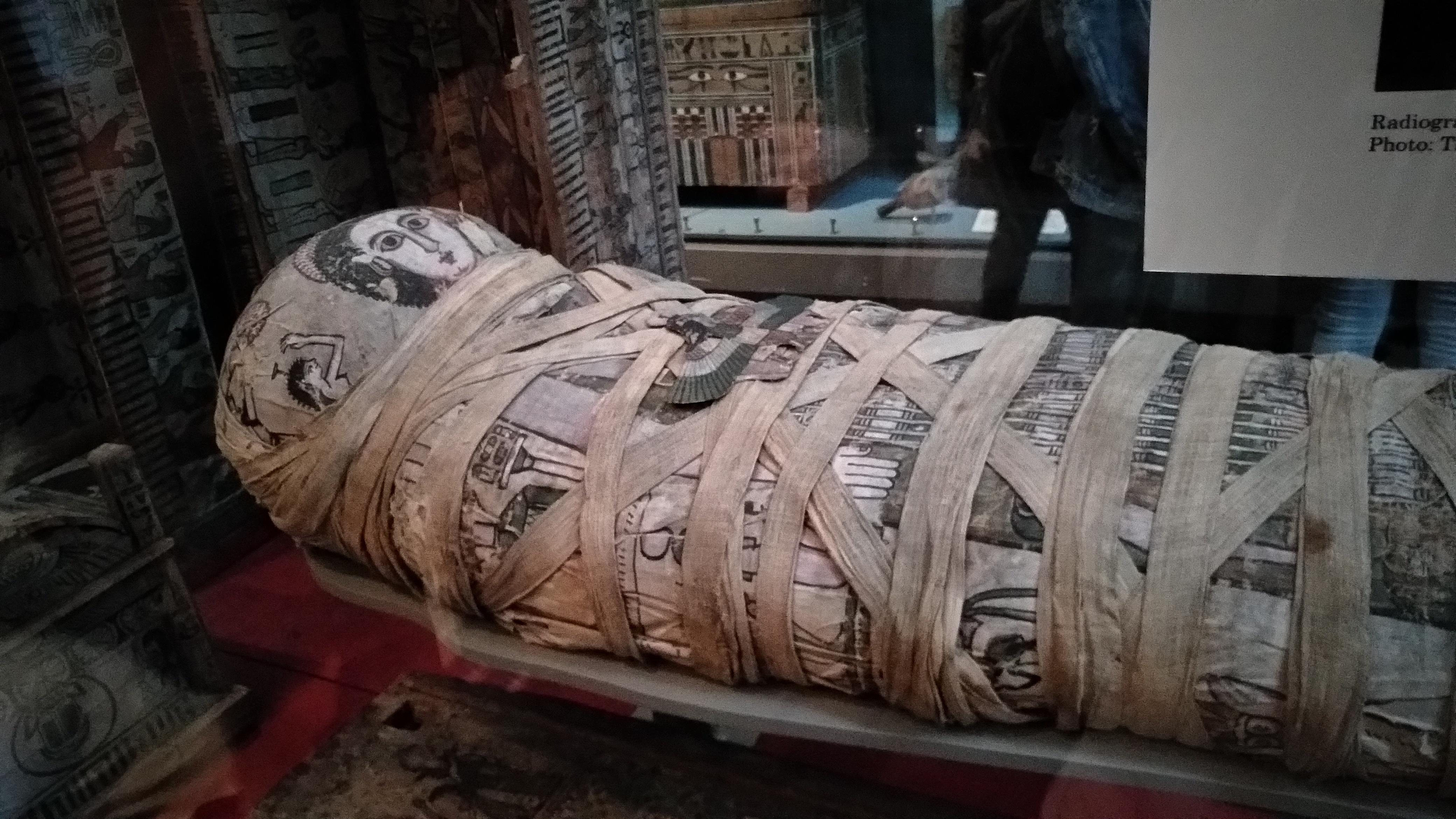

- When we think about the ancient Egyptian civilizations, we envision the massive and towering pyramids, intricately carved gold jewelry and artwork, and carved or painted stories of the Egyptian culture using hieroglyphics. Inside those pyramids, often surrounded by gold, lie carefully preserved mummies, safeguarding the deceased soul so that it may continue living in the afterlife. But what did that ancient world smell like?

- Smell is a powerful link to memory and emotion but one of the first senses to fade from history.

- Ancient Egyptian embalming rituals were rich in scent, yet we’ve long been left guessing what the dead were actually anointed with.

- Now, researchers have uncovered the chemistry of 3,500-year-old embalming ointments and are conducting a cross-disciplinary analysis of their smell.

- The ancient Egyptian society had a very rigid hierarchy with the pharaoh at the apex, followed by nobles, priests, scribes, soldiers and other skilled workers, with a large peasant class and slaves at the bottom.

- The king, or pharaoh, had complete power, leading the people, maintaining order, and serving as a link between the Egyptian people and their gods.

- The afterlife was a central belief in their religion and proper funeral practices, including mummification and burial were crucial for ensuring safe passage to the afterlife.

- While all Egyptians believed in the afterlife, mummification practices varied by social class. The wealthy and powerful received elaborate embalming and tombs, while common people were often buried in simpler ways, sometimes preserved naturally by the desert.

- In a previous EarthDate, we learned that some mummies may have been preserved with salt, but for the upper levels of society, mummification was more involved.

- The internal organs, except the heart, were removed from the washed body and placed in ceramic jars, called canopic jars, specially made to preserve the organs.

- The brain was also removed, often through the nose, although not usually preserved.

- The body was dried using natron salt, a natural mixture made mostly of soda ash and baking soda.

- Next, the body was wrapped in layers of linen with amulets, or charms, placed between the fabric.

- As a final layer of protection, resin was applied, and the mummy was placed in a coffin and tomb.

- But did it smell? Multiple studies are showing that there certainly was a smell, but most likely, it was very pleasant.

Canopic jars were used to store and preserve the internal organs of the deceased. Each jar was associated with one of the Four Sons of Horus, a group of deities believed to protect the organs. Each jar held a specific internal organ—the stomach, liver, lungs and intestines.

Credit: Yair-haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- At Saqqara, the largest archeological site located south of Cairo, scientists unearthed ceramic canopic jars and linen wrappings from an ancient Egyptian embalming workshop.

- Dating back to roughly 600 BCE, over 100 ceramic vessels were found, many with hieroglyphic inscriptions of their contents.

- Chemical analysis of the resins that coated the vessels allowed researchers the ability to identify their contents and revealed some surprising details.

- Thirty-one ingredients were identified from the chemical tests, the origins of which hint at the vastness of the Egyptian empire at the time.

- One resin was from the elemi tree (Canarium luzonicum), native to the Philippines.

- Dammar resin comes from trees in the Shorea genus, which grow in the rainforests of India and Southeast Asia.

- Another resin was from a flowering plant of the cashew family (Pistacia) that is native to Africa and Eurasia.

- Other resins included oils and tars from coniferous plants such as pine, larch and cedar, beeswax, bitumen and animal fats.

- Some of the vessels were labeled with instructions such as “to put on the head.”

- Researchers were amazed at the anatomical knowledge of the embalmers and their expert use of chemicals to reduce moisture, prevent odors and prevent bacterial growth.

The Tomb of Aline was excavated by a German archeologist in 1892. It contained eight mummies, three of which were adorned with mummy portraits and presumed to be the mother Aline and two female children.

Credit: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Another cross-disciplinary team of chemists, archeologists and historians studied nine mummies from different time periods in Egypt. Some of the mummies were on display at museums while others were in storage.

- Scientists captured tiny whiffs of air from around the mummies and used analytical chemistry tools to break down the scent.

- One technique, gas chromatography, separates and differentiates the various smell molecules.

- Another, high-resolution spectrometry, acts like a molecular identification scanner, showing exactly what those mystery scents are.

- The results revealed two scent timelines:

- Present were original embalming materials, including resins, oils and plant-derived substances. These would have been the embalming substances used at the time of death.

- Also detected were later conservation chemicals, substances applied in the 19th and 20th centuries to preserve, protect or deodorize mummies after they were excavated.

- To complement the chemistry, trained human volunteers, super-sniffers, also documented the aromas.

- Most of the super-sniffers agreed with experts who work with mummified bodies, reporting the smells were “woody,” “spicy” and “sweet.” A smaller percentage reported “stale, rancid” odors.

- Overall, the assessed smell was “slightly pleasant” with “woody” and “spicy” the most pronounced.

- Historians contributed important context by helping researchers interpret when and why specific substances were used in embalming. Their insights suggest that choices in scents and materials may have varied based on social status.

- Scientists captured tiny whiffs of air from around the mummies and used analytical chemistry tools to break down the scent.

- Knowing the exact ingredients used in embalming helps conservators understand how these materials age and how best to protect them today.

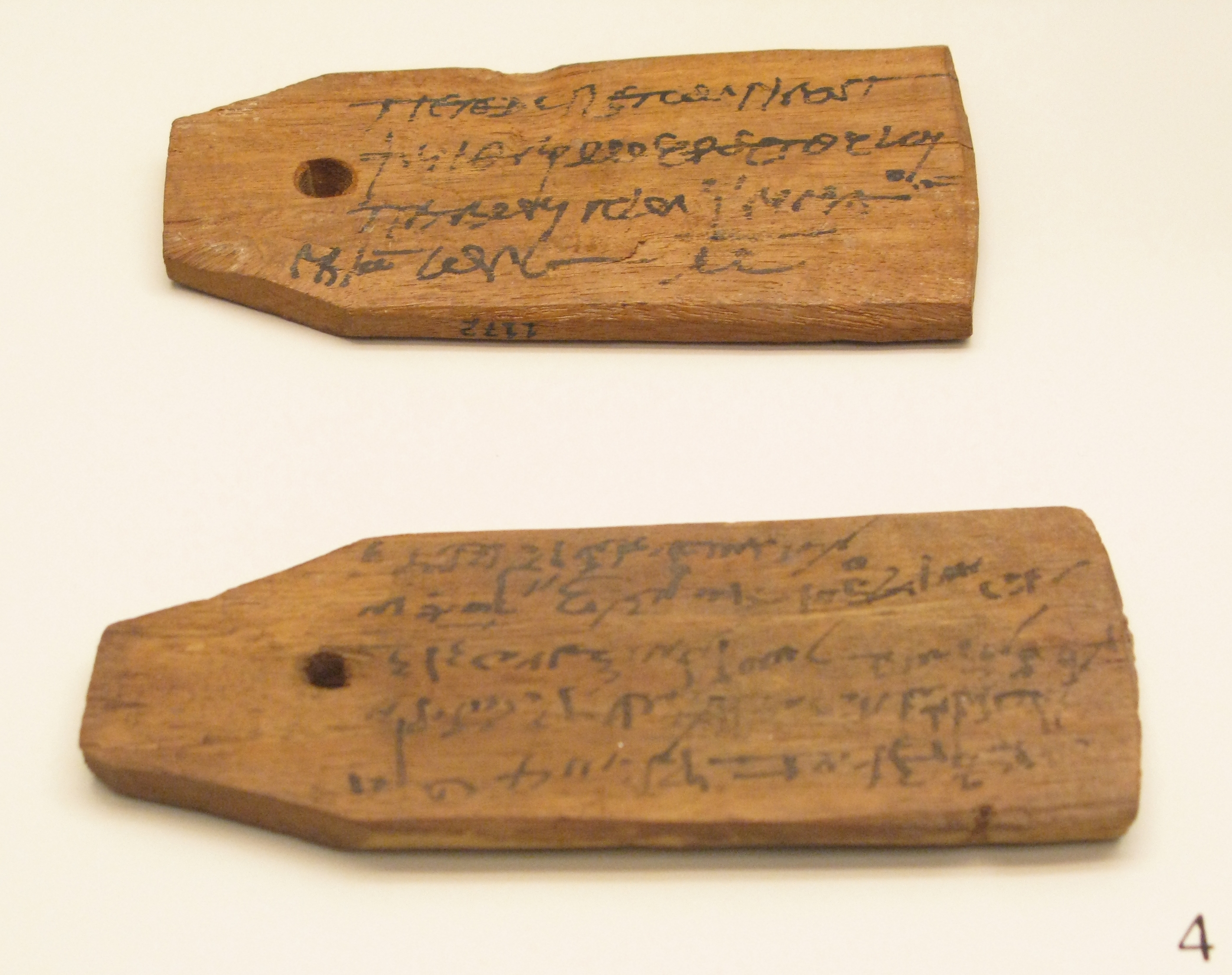

Special priests served as embalmers, overseeing the complex religious rituals and preservation process that took seventy days. These wooden tablets were used to identify bodies, record the names of sacred oils, and even document work attendance.

Credit: Tilemahos Efthimiadis, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons- Identifying the chemical “fingerprints” of both ancient balms and modern contamination allows museum staff to:

- Distinguish original preservation methods from later additions.

- Adjust conservation techniques to be more compatible with ancient substances.

- Minimize degradation caused by previous treatments or storage environments.

- By uncovering how mummies were originally preserved, researchers can make better choices about how to protect them now and in the future.

- Identifying the chemical “fingerprints” of both ancient balms and modern contamination allows museum staff to:

- Based on the chemical findings from the Saqqara tomb, researchers worked with perfumers to recreate the scent of the embalming mixture used over 3,500 years ago.

- This scent, dubbed “The Scent of Eternity,” was composed using molecules identified in the balm including damar resin, elemi, cedar oil and pistachio resin. (Sorry to report that at present, the perfume is not for sale.)

- The sensory reconstruction of an ancient ritual offers a new way to experience the past.

- This research opens doors to multisensory museum displays, where visitors could engage with ancient Egypt through scent, not just sight.

- With a blend of chemistry, history and human curiosity, researchers are bringing us closer to the lived experience of ancient people—molecule by molecule, scent by scent.

Episode script

Pause for a moment to ponder what a mummy smells like. Stinky? Musty? Dusty?

What if I told you ‘woody, spicy and slightly sweet.’ Apparently, that’s what mummy archeologists and scent-expert ‘super-sniffers’ find.

The discovery of an Egyptian undertaker’s 3,500-year-old workshop helped researchers understand why.

When pharaohs or Egyptian nobles died, they could afford elaborate embalming rituals to prepare for a transition to the afterlife.

First the body was washed. Then all organs but the heart were removed and placed in special jars. The lungs, liver, stomach and intestines were each preserved in their own ceramic resting places.

The body was then dried using a mixture of ash and baking soda to preserve it and stop most bacterial decay.

Then it was wrapped in many layers of bandages, and finally coated in fragrant tree resins, which would bond with the linen.

Scientists analyzed the many resins found in the ancient workshop, and discovered they came from plants across the vast Egyptian empire and its trading routes into India, Africa and the Philippines.

They went so far as to work with modern perfumers to recreate the smell of the mummy embalming blend. They combined resins from damar, elemi, cedar and pistachio to create a fragrance they dubbed, wait for it, “Scent of Eternity.”

But if you’re dying to smell like a mummy, unfortunately, the perfume is not yet on the market.