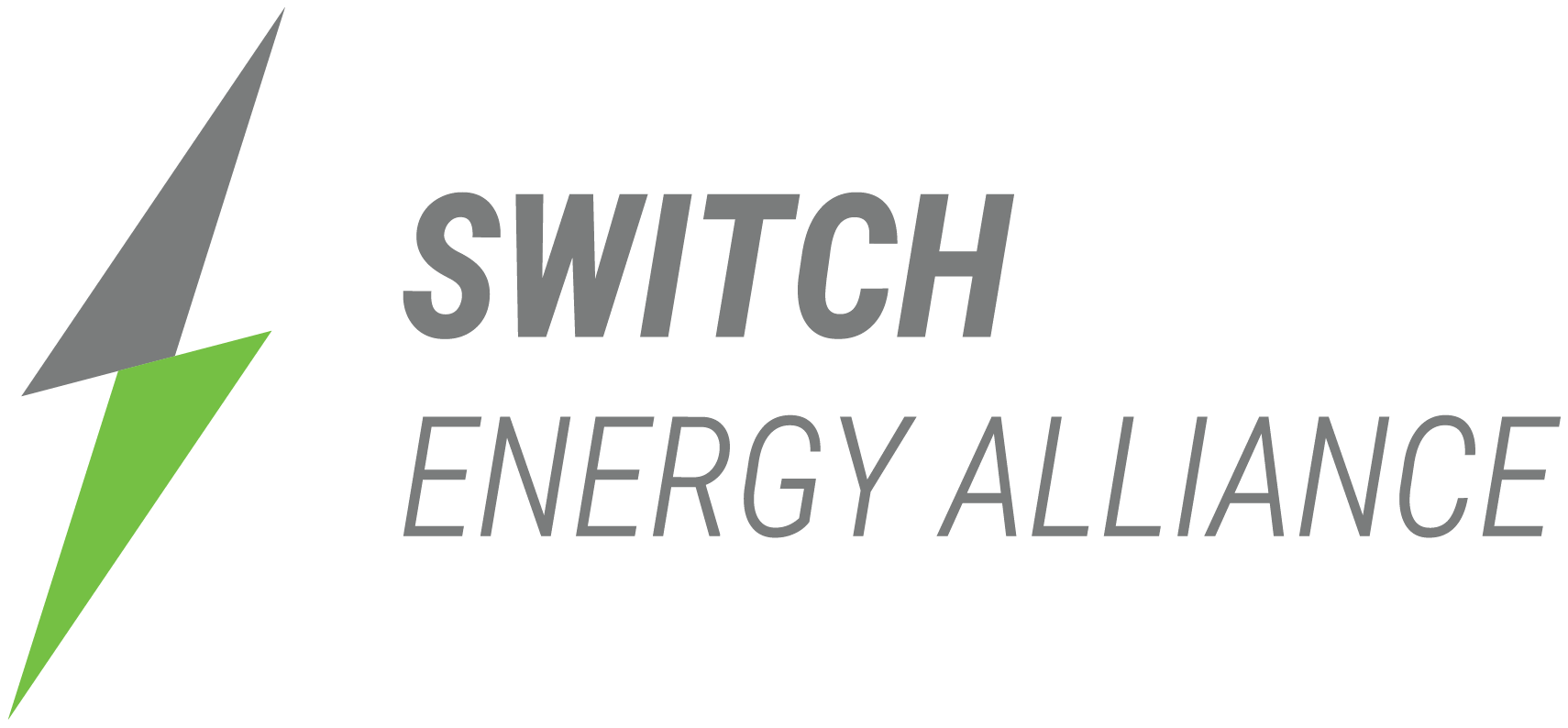

Credit: Unknown (presumably Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh) (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Right: From John Wesley Powell’s second expedition in the Grand Canyon: "Noon Day Rest in Marble Canyon," 1872.

Credit: John K. Hillers (NPS page file) (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

On their maps of the West, Lewis and Clark called it “the Great Unknown.”

For a one-armed geologist named John Wesley Powell, that was too much intrigue to ignore.

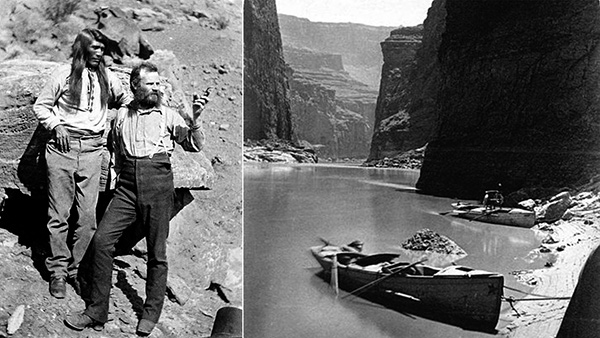

So in 1869, he led a team in four wooden boats on an expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers, destined for what the Spanish called El Gran Cañon.

Within 2 weeks, a rocky rapid had destroyed one of their boats.

Within 2 months, most of their supplies were lost. Fortunately, the lightened boats rode higher in the dangerous waters.

Once in the canyon, the rapids echoed in a deafening roar. At times, the men climbed the walls to sleep in the relative safety of rock ledges.

At one point, the party was unable to portage their boats around a seemingly impossible stretch of rapids.

Three men refused to go further and tried to climb out of the canyon, while Powell and the others took two boats and pressed on.

Powell’s group made it through alive and signaled for the others to take the last boat—but the three men were never heard from again.

After 99 days, Powell and his remaining team reached their destination, but he had lost many of his records from the trip.

Unsatisfied, he returned 2 years later to do it again!

These remarkable journeys, as bold as Lewis and Clark’s Discovery Expedition, launched a movement to declare the Grand Canyon a national park.

Background

Synopsis: John Wesley Powell was a visionary nineteenth-century American scientist whose exploration shaped the settlement of the American West. In 1869, he led the first expedition of European American explorers on a wild ride from Green River, Wyoming, through the canyonlands of the Green and Colorado Rivers, and finally through the Grand Canyon itself. Two years later, he mounted a second expedition to map and photograph the magnificent landscape, opening the region to the American public.

- Powell was born in 1834 in Mount Morris, New York, to English immigrant parents—struggling small farmers who moved frequently throughout his childhood around the states of Ohio, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

- Powell was a self-taught scientist and a self-directed adventurer with a strong childhood interest in nature.

- He rowed the entire Mississippi River at age 21 and made additional exploratory trips on the Ohio and Illinois Rivers.

- Powell taught in country schools in Wisconsin and Illinois; in 1858, he became secretary of the Illinois State Natural History Society.

- In 1861, Powell’s strong antislavery views drew him to enlist in the Union Army as the Civil War escalated.

- He was promoted rapidly to artillery captain, but just 6 months after he joined, at the Battle of Shiloh, a musket ball struck his right arm, which was amputated below the elbow. He returned to active duty and was promoted to the rank of major until his discharge in 1865.

- After the Civil War, Powell returned to academic pursuits as a professor geology and natural history at Illinois Wesleyan and the State Normal University of Illinois.

- He formed the Illinois State Historical Society and was able to secure funding for field research in the Rocky Mountains, leading two expeditions to the mountains of Colorado in 1867 and 1868 to collect specimens of flora, fauna, and minerals.

- While on the Colorado expeditions, Powell met a guide who told him about the uncharted and mysterious river canyons of the Colorado Plateau.

- The Colorado River drains the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona.

- The canyon preserves an amazing geologic record of events on the North American craton through every era from Precambrian to Cenozoic time.

- The North Rim of the Grand Canyon is 8,200 ft above sea level; the South Rim is 7,000 ft above sea level, with a depth of up to 6,100 ft.

- The canyon is 277.7 miles long with a deep, narrow gorge cut by the river, but landslides and erosion have widened some parts of the gorge to 18 miles.

- Before Powell’s excursion in 1869, Congress had written off the territory as having no commercial value and regarded it as too arid to farm, although it had long been the domain of Native Americans.

- The Hopi and Pueblo Native American tribes were early inhabitants of the region; the Apache and Navajo people arrived in the thirteenth century.

- The first European excursion to the canyon occurred in September 1540, when conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (on a quest to find the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola) sent a scouting party with Hopi guides toward the Grand Canyon to see if his party could be resupplied by ship along the river; members of the party called the canyon impassable.

- During Lewis and Clark’s famous Discovery Expedition from 1804 to 1806, the region of canyonlands of the Colorado Plateau was simply left as a blank space on their maps, designated as “ the Great Unknown.”

- In 1857, First Lieutenant Joseph Ives of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was sent to determine if the Colorado River could be used as a resupply route for military maneuvers near Utah (the “Mormon campaign”).

- Ives reported that the scenery was astounding but that the canyon region was valueless agriculturally and that the Colorado River “along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited.”

- However, a scientist on the same expedition, John Strong Newberry, reported, “Though valueless to the agriculturist … [it has the] most splendid exposure of stratified rock in the world”; Newberry was also the first to attribute the canyon formation to erosion by water.

- Powell’s 1869 expedition was planned to produce the first maps and detailed scientific descriptions of the Green and Colorado Rivers in the uncharted canyons of the Colorado Plateau.

- Powell studied reports from Ives 1857 expedition to plan the trip.

- He garnered financial support from the Illinois Natural History Society, the Smithsonian Institution provided scientific instruments, and Congress authorized the U.S. Army to donate military rations.

- He cobbled together a nine-member group of former trappers, mountain men, and Civil War veterans as his excursion team.

- Excursion vessels consisted of four rowboats with round bottoms.

- Three identical freight boats (21 ft long and 4 ft wide) were made of sturdy but heavy oak with covered bulkheads for storage. These were loaded with over 7,000 lbs of supplies, enough for a 10-month expedition.

- Powell’s pine guide boat was 16 ft long and equipped with a leather strap and a chair on top of the deck so he could sit or stand high enough to spot rapids.

- The Transcontinental Railroad had been completed in Utah just 2 weeks earlier, allowing Powell to ship the four boats directly to the departure site from Chicago. The Union Pacific Railroad donated the shipment costs.

- On May 24,1869, at the age of 35, Powell and his team set out from Green River Station, Wyoming Territory.

- Within 3 days, the expedition reached the Uinta Mountains, where the men named and explored the Flaming Gorge of the Green River and nearby canyons.

- The Uinta Mountains are where Powell developed his famous theory of antecedent rivers: that as rocks were uplifted, pre-existing streams and rivers cut down through the strata at the pace of the uplift. The Green River cuts straight down through the eastern flank of the Uinta Mountains, so Powell reasoned that the river must have been in place before the mountains rose.

- Just 2 weeks into the trip, at Disaster Falls on the Green River, one boat and its supplies were lost.

- Critical supplies—including the expedition’s barometers, used to figure altitude for maps and determine remaining vertical drop for the trip—went overboard. Luckily, two of the barometers were recovered.

- Traveling along uncharted rivers was treacherous, with the party portaging around or passing through dangerous rapids and getting caught in spinning eddies. They suffered repeated incidents of splintered oars, as well as soaked or spoiled supplies when the boats took on water or capsized.

- About 3 weeks into the trip, the one-armed Powell almost met an untimely end stranded between widely spaced footholds on a vertical cliff face—luckily, he was saved by a crew member’s long johns!

- Powell could not release his single-handed hold without falling; his teammate quickly thought to remove and lower his leggings to Powell from an overlying ledge, hauling him up to safety.

- On June 28, the team reached the mouth of the Uinta River.

- There, the men resupplied at the Uinta Indian Agency, where crops of corn, wheat, potatoes, and even red currants were thriving on Native American farms and cattle ranches.

- On July 16, they reached the confluence of the Green River with the Colorado River.

- Their original 10-month supply of rations had by now been reduced to only 2 months of remaining supplies because of losses and spoilage—but the load-lightened boats rode higher in the water, making passage of whitewater sections easier.

- They continued through dangerous rapids, with canyon walls towering more than 2,000 ft above their heads.

- On August 10, the team made it to the mouth of the Little Colorado River, about 700 miles from their start at Green River Station.

- Here, they repaired their boats, dried their provisions, and recorded the dimensions of the canyon for 3 days.

- Their remaining supplies included only stale apples, bacon, flour, and coffee.

- On August 13, they departed from their camp at the true entry into “the Great Unknown,” at what Powell called the “foot” of Grand Canyon.

- Powell referred to the canyon as “our granite prison,” with one rapid following another, creating a deafening roar in a canyon with mile-high walls.

- The men had to scale the canyon walls for fitful sleep on shelves 40–50 ft above the river.

- On August 27, they reached what Powell would later name Separation Canyon; its massive walls of blackened rock lacked any way to portage the boats downstream.

- The team had provisions for only 5 more days and was faced with a cataract of 18–20 ft, followed by 300 ft of rocky rapids.

- Powell knew they were only 45–90 miles from their destination—Mormon settlements on the Virgin River.

- Three men believed that going on by river was too dangerous. On August 28, they left the expedition, climbing out of the canyon with a plan to walk to Mormon settlements.

- The remaining six men abandoned Powell’s small guide boat and were able to run the rapids safely in the remaining two 21-ft boats. The three climbers were never seen again and are presumed to have perished.

- On August 29, the group passed the Grand Wash Cliffs, where the canyon walls receded and the river calmed. On August 30, they found the mouth of the Virgin River, reaching safety at the Mormon settlement of St. Thomas on August 31—the end of an epic adventure begun 99 days earlier.

- Within 3 days, the expedition reached the Uinta Mountains, where the men named and explored the Flaming Gorge of the Green River and nearby canyons.

- Powell had lost many of his notes and samples during the first voyage, so he was not satisfied with its scientific results.

- Powell began a lecture tour that popularized the “Grand Canyon” name (it had previously been referred to as the “Big Canyon”) as he described his discoveries and fundraised for a second expedition, which was underwritten this time by the U.S. government.

- The second expedition departed May 22, 1871, from the same launch point at Green River Station.

- The ten crew members included two photographers and a cartographer for careful documentation and mapping of the canyon.

- Numerous photographs of the canyons were produced during this trip, and artists from the Smithsonian Institution rendered many into illustrations to enable publication using printing methods of the day.

- The crew also collected topographic data and precipitation records and cataloged flora and fauna of the region.

- The team entered the Grand Canyon at Lee’s Ferry on August 17, 1872, arriving at the end of their voyage on September 7, 1872.

- After his second voyage, Powell traveled throughout the country lecturing about the canyon to promote it as a natural wonder.

- He published his first account of the voyages, Report on the Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries, in 1875. In 1895, the book was revised and reissued as The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons.

- In 1881, Powell was named the second director of the United States Geological Survey.

- During his tenure, he promoted geologic mapping of the entire nation.

- He recommended creating western state lines along the boundaries of watersheds to avoid future disputes. (We’ll talk more about his amazing foresight in another EarthDate episode.)

- He developed the color scheme geologists still use today to illustrate the ages of rocks on geologic maps.

- He retired from the USGS in 1894 but went on to become Director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology.

- John Wesley Powell died on September 23, 1902, at the age of 68, but the Grand Canyon that he explored lived on!

- In 1893, President Benjamin Harrison established a forest preserve in the region.

- In 1903, President Teddy Roosevelt first visited the Grand Canyon, subsequently establishing the Grand Canyon Game Preserve in 1906, and then adding adjacent forestlands and declaring it a National Monument in 1908.

- Although mining interests blocked the legislation for 11 years, President Woodrow Wilson was finally able to establish the Grand Canyon National Park as our 17th U.S. National Park on February 26, 1919.

- In 2018, over 6 million people from the U.S. and around the world visited the park—hopefully via treks less strenuous than Powell’s had been!