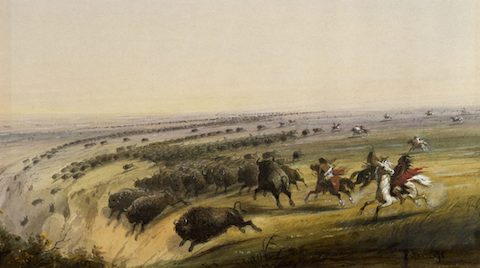

Plains Indians depended on buffalo for everything: meat for food, hide for clothing, horns and bones for weapons and tools.

One of the ways they hunted them was by stampeding them over cliffs.

Scientists thought that humans practiced communal hunting drives like this as far back as 5,000 years ago. But a recent discovery has changed that.

When constructing a new airport north of Mexico City, workers unearthed enormous bones and called in scientists, who discovered two massive pits 80 feet in diameter.

They realized the 800 bones within the pits had come from woolly mammoths. There were herds that lived in the area long ago.

They were also able to determine, based on sediment layers deposited within the pits and tool marks on their walls, that humans had dug them 15,000 years ago, by hand.

It appeared that early tribes had driven the giant beasts into them, trapping them for slaughter.

Like the Plains Indians, these hunters were resourceful with the animals, turning bones into knives and scrapers, which they used in butchering. Some of these were found in the pits.

It also appeared that many generations of humans hunted mammoths here, using this site for more than 500 years.

When they finally abandoned the pits, they left the mammoth bones artfully arranged inside, with tusks and shoulder blades encircling skulls, perhaps in tribute to the animals that fed and clothed them for centuries.

Background

Synopsis: Researchers appear to have underestimated the hunting prowess of prehistoric humans, assuming they could only hunt the huge megafauna of the Pleistocene if the animals were already compromised or injured. But recent finds show that as many as 14,700 years ago, hunter-gatherer bands of humans deliberately trapped woolly mammoths in hand-dug pits and may have used the same pits repeatedly for more than 500 years.

- In early 2019, while excavating for a landfill at the site of a future airport near the town of Tultepec, north of Mexico City, crews discovered some huge bones and called upon scientists from Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) to investigate.

- Ten months later, the researchers had unearthed prehistoric pits filled with the remains of woolly mammoths—more than 800 bones from at least 14 animals.

- The Tultepec II excavation site is now considered one of the world’s “mammoth megasites” (sites where numerous mammoth bones are found).

- Researchers had previously found evidence of at least five mammoth herds in the region that lived alongside herds of prehistoric camels and horses.

- Ash layers from Popocatépetl, a nearby volcano, were found above and interlayered with the mammoth remains. The ash was dated at around 14,700 years old and documents about 500 years of volcanic activity.

- About 15,000 years ago, the area was a dried-up lakebed during the climatic instability of the Pleistocene Epoch. Centuries later, interglacial flooding filled the pits with lake sediments, which solidified.

- The large excavation (120 ft × 300 ft × 24 ft, or 40 m × 100 m × 8 m) into the flat-lying sediments of ancient Lake Xaltocan revealed pits with vertical walls that appear to have been dug by humans to trap the great herbivores.

- The two pits discovered so far are 5.5 ft deep (1.7 m) and 82 ft (25 m) in diameter and contain 824 bones, with eight mammoths found in the southern pit and six found in the northern pit.

- This evidence that early humans intentionally dug mammoth traps changes our fundamental understanding of their social organization.

- Researchers envision groups of between 20 and 30 hunters chasing the animals into the pits, where they were trapped for slaughter for meat and tools.

- Humans sharpened rib bones to use as knives to cut the mammoth meat and they polished other bones to help remove fat from the skin.

- But humans also appear to have honored the animals, as shown by the arrangement of some of the bones. Some shoulder blades and tusks were aligned artistically around the skull of an animal. In other cases, right shoulder blades were lined up together, while left shoulder blades were not collected, possibly indicating a different connotation about the right sides versus left sides of animals.

- Although the idea of game drives had not previously been thought to date back to the days of mammoths, we know that Native Americans hunted bison for thousands of years using a similar hunting strategy that would force herds of animals off cliffs in a death plunge.

- Tribes dried the meat for food and used the hide, sinew, and horns to make clothing, bedding, shelter, weapons, and tools.

- Evidence of this communal hunting technique ranges from more than 6,000 years ago into the mid-1800s. One of the best-preserved sites is now a UNESCO World Heritage site: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in southern Alberta. At the site, visitors can still see the lanes that natives used to drive the bison over the cliffs.

- Although he never witnessed one, explorer Meriwether Lewis described a “buffalo jump” in one of his journals from the Lewis and Clark Expedition:

- “One of the most active and fleet young men is selected and disguised in a robe of buffalo skin ... he places himself at a distance between a herd of buffalo and a precipice proper for the purpose; the other Indians now surround the herd on the back and flanks and at a signal agreed on all show themselves at the same time moving forward towards the buffalo; the disguised Indian or decoy has taken care to place himself sufficiently near the buffalo to be noticed by them when they take to flight and running before them they follow him in full speed to the precipice; the Indian (decoy) in the meantime has taken care to secure himself in some cranny in the cliff ... the part of the decoy I am informed is extremely dangerous.”

- The INAH researchers in Mexico plan to search for additional mammoth traps using radar surveys in the Tultepec region, especially in three sites where villagers have found mammoth bones in recent years.