Credit: By USFWS Mountain-Prairie - Pronghorns Crossing Highway on Seedskadee NWR., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46831826

Background

Synopsis: Wildlife rely on natural corridors, but roads and development break those routes and cause collisions. By mapping paths and installing species-appropriate crossings, these important habitat corridors are being reconnected, restoring safe movement and reducing risk.

- Across mountains, rivers, and plains, the landscape once read like an open map for wildlife on the move. Animals followed seasonal routes to food, water, and breeding grounds.

- Some journeys stretched thousands of miles, while others paused at a single path to a vernal pool.

- Today, highways, fences, and growth cut those lines, turning journeys into dead ends and collisions. Reconnecting that map with corridors and wildlife crossings brings those routes back to life.

- Highways, bridges, fences, and dams help people, but they block animals from reaching food, water, mates, and shelter.

- The once-safe landscape is broken into small, isolated patches, creating problems for animals and people.

- Roads split populations and turn crossings into crash zones.

- The U.S. sees an estimated 1-2 million collisions with large animals every year.

- One analysis put total vertebrate roadkill near 365 million per year.

- Fragmentation traps wildlife on “islands” leading to inbreeding and poor survival.

- This has been documented with both Florida Panthers and Southern California mountain lions.

- Inbreeding has created a population with physical defects, reproductive issues, increased risk of disease, and eventually, population extinction.

- When cities and suburbs expand, narrow pinch points force many animals through the same gap, making them much more vulnerable to predators, vehicles, and people.

- Migration can also be a problem for amphibians.

- In the spring, salamanders and frogs migrate from upland forests to vernal pools. Roads often slice across these routes, increasing mortality of these amphibians.

- Ecological corridors are connected regions of habitat that link areas so that animals can move safely between them.

- They are used to meet daily or seasonal needs and are shaped by behavior and biology. Some are learned paths, inherited navigation cues, or the result of seasonal timing.

- Both the landscape and vegetation determine the paths of migration. Animals may follow certain tracts for cover or forage, and use valleys, riverbanks, or ridgelines as guides.

- Corridors exist at many scales, from continental migration pathways to short links between a roost and a feeding area.

- Paths between daytime and nighttime resting spots, feeding areas, and watering sites are corridors too.

- They can be used individually or by a large group. A single bear may follow a habitual path, while an entire herd of elk share a seasonal route.

- Species need different corridor qualities. Herd animals like elk and deer favor open sight lines, carnivores prefer areas with lots of cover, and amphibians need moist and shaded ground.

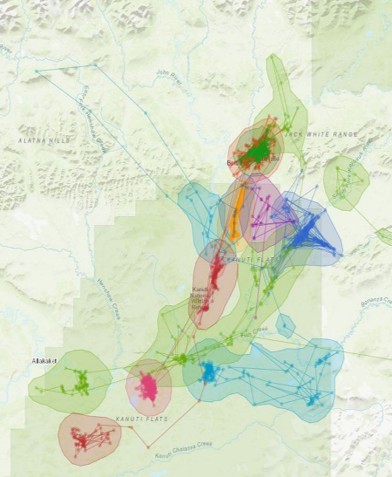

- Signs of corridors include repeated tracks, GPS-collar paths, camera detections, and known crossing hot spots from local or indigenous knowledge.

- Physical features can funnel or deflect movement. Roads, fences, rivers, and steep cliffs often pinch animals into narrow routes.

- Effective corridors connect to viable habitat at both ends and remain permeable through seasons, droughts, snow, fire, or land use.

Credit: Mark Bertram/USFWS, Public Domain

- Because development fragments natural corridors, crossings are required to bridge the gaps.

- Crossings are human-made structures that let animals move safely across barriers such as roads, rail lines, and buildings, reconnecting habitat that has been split.

- They reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions and mortality, improve human safety and restore movement within mapped corridors.

- Crossings are installed at areas known as pinch points and along established corridors where animals historically cross.

- Types of crossings include:

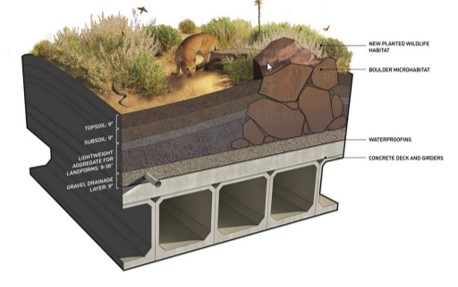

- Underpasses – tunnels, bridges under crossings, and large culverts that allow wildlife to pass beneath traffic.

- Overpasses – vegetated bridges that carry habitat over a roadway or railway.

- Adapted structures – existing culverts or similar features that animals can safely use, when sized and configured appropriately.

- The design of the crossing must appeal to the needs of the creatures using the crossing.

- Open, wider spans for herd animals; more cover and quieter approaches for wary carnivores; dark, moist passages for amphibians.

- Soil, plants, and natural substrates encourage use; good light and drainage keep structures inviting.

- Fencing and approach design steer animals to the crossing and away from traffic.

- Corridors are the routes or habitat linkages animals use to move between core areas while crossings are the engineered links placed within those routes to help animals navigate specific barriers.

- Wildlife crossings were first introduced by the French in 1950 and other European countries quickly followed suit.

- The Netherlands boasts more than 80 wildlife bridges and thousands of animal tunnels.

- The world’s longest wildlife crossing is the Dutch Natuurbrug Zanderij Crailoo bridge, an impressive sight at 50 m (164 feet) wide and over 800 m (2625 feet) long. It spans a highway, railroad, sports complex, and business park.

- The Netherlands boasts more than 80 wildlife bridges and thousands of animal tunnels.

Credit: By Tegethof - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1389361

- The Trans-Canada Highway through the Bow Valley in Alberta became a lethal barrier by the 1970s, with roughly 100 large animals killed each year. In the early 1980s, the road was expanded from two lanes to a divided four-lane highway.

- Parks Canada used the project to test ways to reduce collisions and reconnect habitat.

- The effort launched the world’s longest road-ecology study across Banff, Yoho, and Kootenay national parks, tracking how wildlife moves and where conflicts occur.

- Over time, 49 wildlife crossings were built including 42 underpasses and 7 overpasses, each at a key pinch point along the highway.

- Over 150,000 animals including bear, deer, elk, and cougar have been spotted using the crossings.

- The result has been a drop in wildlife-vehicle collisions of more than 80 percent overall, and over 96 percent for elk and deer. The success of the program has driven wider adoption of crossings across Canada.

Credit: By m01229 from USA - Animal crossing overpass in Banff National Park - Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64420398

- The U.S. has been expanding the application of wildlife corridors over the past 35 years.

- One of the oldest amphibian crossings is in Amherst, Massachusetts where two, 6-inch-wide tunnels assist yellow spotted salamanders across the road.

- Salamanders, as well as other wood frogs and spring peepers, use springtime vernal pools to breed and lay eggs.

- During this busy travel season, 9-18 inch “fencing” guides the amphibians to the tunnels where they have safe passage between the vernal pools and the drier uplands.

- Since 2000 Arizona has built at least 20 wildlife corridors, including 17 underpasses paired with funnel fencing.

- On a 17-mile elk migration stretch, collisions dropped by about 90% after the underpasses and fencing went in.

- Near Tucson, the Oracle Road project added a wildlife bridge and underpass (about $9.5M) to reconnect habitats between the Santa Catalina and Tortolita ranges.

- In Washington state, the Snoqualmie Pass East effort spans a widened six-lane section with multiple undercrossings and the Keechelus overcrossing.

- Deer were using the bridge even before it was landscaped, and by the end of 2023 cameras had recorded 25,000+ safe crossings, including elk, deer, coyotes, and cougars.

- One of the oldest amphibian crossings is in Amherst, Massachusetts where two, 6-inch-wide tunnels assist yellow spotted salamanders across the road.

Credit: Anneberg Foundation, News Release (will need to check on permission to use)

- In California, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing over US-101 at Liberty Canyon is designed to be the nation’s largest wildlife bridge. At roughly 210 feet long (64 meters) and 174 feet wide (53 meters), the bridge crossing will feature native vegetation along with sound and light buffers. Completion is expected in 2026.

- It sits in a densely populated metro corridor where an estimated 300,000 vehicles per day use this stretch of freeway. Reconnecting habitat here will provide important safety and ecological benefits.

- The $92 million project is being funded through a public-private partnership led by the Anneberg Foundations, California Wildlife Conservation Board, and the National Wildlife Federation’s #SaveLACougars campaign.

- Science supports the need for a crossing at this location. Since 2002, National Park Service biologists have tracked and studied over 100 mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains.

- They have documented evidence of severe genetic isolation and models warn that local extinction would occur within 50 years without connecting habitats.

- Big and small, furred or feathered, scaled or winged, animals still need room to move. As the human footprint expands and paths shrink, corridors and wildlife crossings stitch the map back together and keep these journeys alive.

Episode script

Each year, U.S. drivers collide with 1 to 2 million large animals, often killing them and endangering the drivers.

Add in smaller creatures, and studies estimate up to 300 million animals die on U.S. roads annually. An astounding number.

This is because wildlife must roam, and always has -- to find food and water, breed and raise young, and migrate seasonally.

They often follow ecological corridors dictated by geography and natural resources.

These pathways could be millennia old. But in the last century, they’ve been dissected by roads and highways.

The result is that either animal populations become isolated in small areas, where they can starve, become prone to disease or inbreeding.

Or they cross roads and court danger.

This has led communities around the world to build thousands of wildlife crossings – bridges or tunnels that guide animals safely across roads, railways, and open development.

They’re usually constructed along existing animal corridors.

While often made of concrete, they’re covered in soil, plants, and rocks to simulate natural habitat.

They can be hundreds of feet long and cost millions of dollars. But their results are astonishing.

They’ve reduced animal mortality in problem areas by more than 90%, and saved drivers from thousands of accidents.

As human development continues to expand, wildlife crossings stitch ecological pathways back together.