Penguins have been around a long, long time.

They first evolved more than 60 million years ago when the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs opened a niche for them.

Fossils suggest they were already flightless, but they took to the sea where they became perfectly adapted:

Their feathers are coated in oil. Their body is insulated in fat. Their wings are shaped like flippers, making some penguins twice as fast as the fastest human swimmer.

Their bowling-pin shape doesn’t look athletic, but in the water they’re a tuxedoed torpedo.

That signature black and white coloring hides them from predators and prey. From above, they blend into the ocean darkness. From below, they look like the white sky.

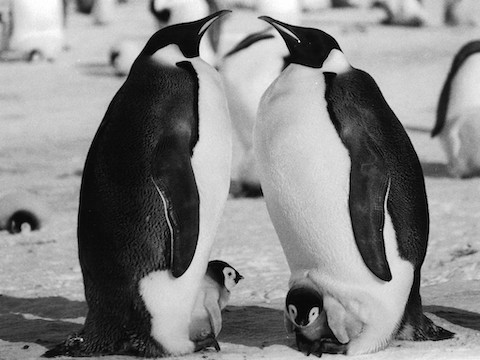

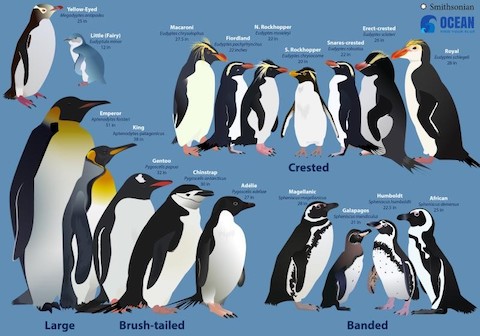

Though some early penguins stood as tall as a human, they’ve diversified into 17 different species, from the largest 80-pound Emperor to the tiny fairy penguin.

Some species spend 75 percent of their time at sea—enough to grow barnacles on their feathers.

Others can dive to 1,500 feet in search of food and hold their breath for half an hour!

Each year around April 25th, the Adélie penguins of Antarctica begin a long migration from their summer breeding grounds to their winter feeding grounds. A few weeks later, their larger Antarctic cousins follow suit.

So, scientists have designated April 25th as World Penguin Day. A good time to celebrate this weird and wonderful swimming bird.

Background

Synopsis: April 25th is World Penguin Day! These well-loved tuxedoed birds have been around for at least 60 million years and may have benefitted from the impactful demise of the non-avian dinosaurs. While comical to watch on land, they are powerful swimmers with surprising grace and ability in the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere.

- There are about 17 species of penguins that live in the Southern Hemisphere, all the way from the equator to Antarctica.

- One species lives just north of the equator. The Galapagos penguins are the northernmost species, living in the Galapagos Islands.

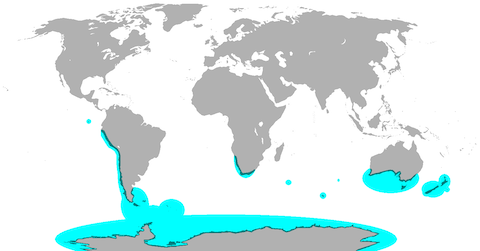

- The largest species, Emperor penguins, can be found in Antarctica along with its smaller cousin the Adélie penguin. These are the only two species living exclusively in Antarctica. Three additional species visit the continent annually.

- Most penguins live in the temperate zone, especially smaller species.

- There are six different types of penguins, all of which wear variations of tuxedo coloring.

- Their tuxedo coloring protects them from predators as they swim in the ocean. From below, their white bellies make them hard to see against the sky, and, from above, their black backs make them hard to see against the ocean depths.

- Penguins range in size from the fairy penguin at just over 1 ft (33 cm) tall to the emperor penguin at about 3 ft 7 in (1.1 m) tall.

- Emperor Penguins weigh in at about 77 lbs (35 kg) and live exclusively in Antarctica. Larger penguins tend to live in colder climates today.

- The little blue penguin is the smallest species, weighing only 2.2 lbs (1 kg). It lives in New Zealand and along the coast of Southern Australia where they are known as fairy penguins. Their Māori name is kororā.

- Penguins are ocean-going birds. They can’t fly, but they sure can swim!

- Penguins waddle comically on land because they are built for the sea. Even on the surface of the sea they paddle around like clumsy ducks.

- Their wings have developed into powerful flippers, their streamlined bodies are torpedo shaped, and their legs and feet act as rudders.

- They spend about up to 75% of their lives in the sea—so much that some species are known to grow barnacles on their feathers.

- Most humans swim about 3 mph (4.8 km/h), with our fastest Olympic times for the short burst of a 50 m freestyle at just 5.16 mph (8.3 km/h).

- The fastest penguins are large emperor penguins that regularly cruise at 7 mph (11 km/h) but can swim in fast bursts (like a 50 m freestyle) at 9 mph (14 km/h), nearly twice as fast as the fastest humans.

- Most penguins swim at around 5 mph (8 km/h) for long distances.

- Tiny fairy penguins swim at around 1 mph (1.5 km/h) when cruising.

- Humans can generally hold their breath for 30–90 seconds, but most penguins can hold their breath for twice that as they porpoise along 3–6 ft (1–2 m) below the surface.

- Most penguins dive to depths of 30–60 ft (9–18 m) to find krill, shrimp and squid for food.

- But larger penguins like the king penguin can dive to 300 ft (91 m).

- Emperor penguins have been tracked to 1,700 ft (520 m) below the surface, and one bird held its breath for more than 32 minutes. That’s an amazing record-setting avian dive!

- It is hard to track them once they are in the ocean, but some penguins have traveled 1,200–4,000 mi (1,800–6,500 km) from breeding sites during annual migration.

- As penguin ancestors developed the ability to swim, they lost the ability to fly.

- The earliest known penguin fossils were found in New Zealand and are about 60 million years old. These Paleocene birds were already adapted to the oceans.

- Their short wingspans of fused and flattened bones suggest they were probably already flightless.

- Researchers speculate they may have adapted to fill an aquatic niche that opened after the demise of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago (ED-096).

- No earlier transitional fossils with the ability to both fly and swim have been found. The closest relatives of the penguin are the petrel and the albatross.

- Some prehistoric penguins from the late Eocene Epoch 37 million years ago stood as tall and weighed as much as a modern human.

- Happy World Penguin Day!

- Every year on around April 25th, the Adélie penguins of Antarctica begin their northern migration from their breeding grounds to follow the sun to their winter foraging grounds. Soon afterward, the larger penguins that breed in Antarctica follow their smaller cousins northward.