Earlier, we talked about the run-up to the greatest natural disaster in American history, the Dust Bowl.

Between 1870 and 1920, settlers poured into the Great Plains, plowed under native grasses, and planted grain.

Then in 1929, the Great Depression struck, and grain prices collapsed. In 1931, a long drought set in.

Farms failed across the region. Millions of acres, stripped of grass and barren of crops, lay untended.

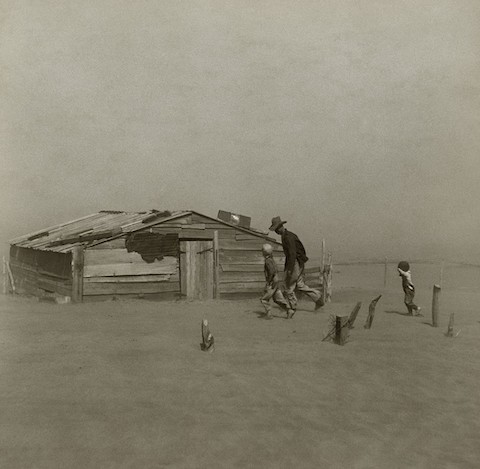

The fierce prairie winds carried the dry topsoil high into the sky in roiling storms of black dust that pummeled farmers and buried buildings.

In 1933, a storm like this came nearly every week.

In 1934, the dust clouds expanded to cover the Midwest.

In 1935, a blizzard of hot, black soil raced across the country at 100 miles an hour, cutting visibility to three feet and blanketing Washington, D.C.

By then, nearly a billion tons of fertile topsoil had been carried off the Great Plains.

The human toll was staggering. More than 3 million people abandoned their farms and businesses and left the Plains, penniless.

Those who stayed suffered: respiratory diseases from breathing dust, hunger so severe they had to eat tumbleweeds.

Infant mortality soared and birth rates dropped to the lowest in U.S. history.

What finally ended the Dust Bowl? We’ll see, in our next and final installment of this story.

Background

Synopsis: The Dust Bowl of the 1930’s was a prolonged natural disaster that caused terrific human suffering and displaced millions of people from the Great Plains, resulting in America’s largest migration in a single decade.

- In the previous EarthDate episode, “Dust Bowl 1: Storm Brewing,” we talked about the perfect storm of natural, cultural, and economic events that aligned for more than a century before America’s great natural disaster in the Dust Bowl.

- The stage was set for disaster when the rain stopped in late 1931.

- With desiccated fields lying fallow, there was nothing to hold the soil in place on millions of acres of over-plowed land. Topsoil that had formed over thousands of years could be blown away in hours.

- In 1932, 14 “black blizzards” of dust were reported, and there were another 38 in 1933. These black blizzards carried millions of tons of fertile black dirt that pummeled anyone and anything that was out in it.

- By May 1934, 75% of the country was under drought conditions and 27 states were experiencing a severe drought.

- On May 9, 1934, a dust storm 1,800 mi (2,900 km) long carried dust from the Great Plains to Chicago, where it deposited more than 12 million lbs (5.4 million kg) of dust. It continued for two days, reaching Atlanta; Washington, D.C.; New York City; and Boston. Dusty red snow fell on New England that winter.

- Almost a year later, on April 14, 1935, a warm, windless day turned into “Black Sunday” when a 1,000-mi (1,600-km)-long maelstrom of hot, dry, coal-black dust raced across the country at more than 100 mph (160 kph), reducing visibility to 3 ft (1 m) and blowing dust more than 200 mi (320 km) out over the Atlantic. When the dust settled, Dust Bowl fields and wells were choked, and vehicles were buried under huge dirt drifts.

- By 1935, it is estimated that more than 850 million tons (770 million metric tons) of topsoil had blown eastward from the Dust Bowl.

- The human toll was profound.

- The drought and catastrophic loss of topsoil caused crop failures, and many farmers who had taken out mortgages for farm equipment faced foreclosures and were forced to abandon their property. More than 500,000 people were left homeless.

- About two-thirds of the citizens of the Great Plains stayed through the hardships of widespread hunger and poverty. Infant mortality soared, and the nationwide birth rate fell to less than 20 children per 1,000 women—the lowest in U.S. history. People learned to brine tumbleweed and eat it to avoid starvation. Deaths from malnutrition and respiratory disorders increased. “Dust pneumonia” clogged respiratory tracts similar to silicosis, and dust transmitted influenza and measles viruses.

- The rest of the Great Plains’ population—more than 3.5 million people—left, the largest human migration in any decade in the United States. They packed their families and belongings into jalopies and headed west to find work, many becoming migrant workers. Nearly one-third of these migrants were professional or white-collar workers such as teachers, lawyers, and small businessmen. Only about 20% came from Oklahoma, but “Okies” became the term for any migrant from the region who had lost everything.

- More people migrated to California during the 1930’s than during the Gold Rush of 1849, overwhelming the job market and straining health services and infrastructure to the point that signs saying “Okies Not Welcome” were posted on the border. Today more than 12.5% of Californians come from Okie heritage.

- It is a sad tale. How would Americans rally to save the Great Plains?

- Our story continues in “Dust Bowl 3: Resolution.”