Credit: By Rjglewis - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7641469

Background

Synopsis: Beneath our feet lies a constant source of heat that can be tapped into for power, but for

most places on Earth, it’s been out of reach, locked away in dry rock, impractical or too expensive to

access, except in restricted areas of the globe. Now, new technology is changing that by making it

possible to engineer geothermal energy systems almost anywhere. Scientists and engineers are turning

inaccessible heat into a promising energy solution.

- Previous EarthDate episodes explored geothermal energy in several forms, each relying on unique natural conditions to bring Earth’s heat to the surface.

- In Hot Springs Eternal, we explored how Earth’s natural plumbing brings underground heat to the surface in the form of hot springs used for bathing, heating, and even cooking.

- In Low-Temperature Geothermal, we looked at how shallow ground temperatures can be tapped by geothermal heat pumps to efficiently heat and cool homes and buildings.

- In Iceland—The Geothermal Pioneer, we traveled to a volcanic hotspot where engineers use supercritical steam to harness extreme underground heat for electricity production.

- Each of these relies on active tectonics, places where nature conveniently concentrates and brings heat anywhere from 500 feet (152 meters) to miles (kilometers) from the surface.

- But now, new technology may make it possible to engineer geothermal systems where those natural conditions don’t exist, expanding the potential for Earth’s heat to be used in many more places.

Credit: By McKay Savage from London, UK - Iceland - Blue Lagoon 09, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23463974

- Natural geothermal systems exist where water in the rock absorbs and concentrates heat and, via permeable paths, brings it closer to the surface.

- Forty-seven terawatts of heat flow out of Earth and into space continually. But that is just a fraction of the potential stored underground.

- Rock holds heat very well. Scientists estimate that the upper six miles (10 kilometers) of Earth’s crust holds thousands of times our current annual energy needs in potentially extractable heat energy, offering a vast reservoir of thermal energy that could be tapped with the right technology.

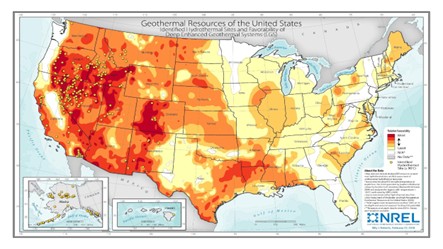

- While hot rock is widespread globally, geothermal energy production requires both concentrated heat and naturally occurring water or steam to carry that heat upward—typically from depths of 1 to 3 kilometers.

- This has made geothermal energy available in only a few select regions such as California, Nevada and Hawaii in the U.S., and globally places like Iceland, the Ring of Fire, New Zealand, and Kenya.

Credit: NREL.gov

- For decades, the hot rock beneath our feet seemed like untapped potential, being too deep, impermeable, or too costly to access. That’s beginning to change with the emergence of engineered geothermal systems (EGS), which aim to make geothermal energy viable in a much wider range of locations.

- Engineered geothermal systems enhance or create permeability in deep hot rock by stimulating small fractures that allow fluids to circulate. This process is like oil and gas fracking but uses tailored pressures to improve heat exchange without the same oil and gas extraction goals.

- Advances in drilling technology developed by the oil industry, including precise vertical and directional drilling, have significantly reduced costs and increased accuracy, making it easier to reach and interact with hot rock at depths of several kilometers.

- Geothermal energy today is used for both electricity and direct heating, with both applications growing steadily over the past century. Engineered systems now expand the potential to produce power from regions that previously lacked sufficient natural permeability or groundwater.

- With support from high-resolution subsurface imaging and real-time monitoring, EGS offers a path to reliable, low-emission energy in areas once considered unsuitable. This flexibility positions geothermal to play a larger role in meeting long-term clean energy and sustainability goals across local, national, and global scales.

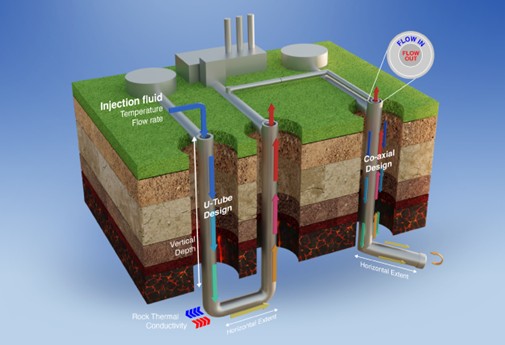

- While EGS extends geothermal’s reach by improving rock permeability, other designs avoid dependence on rock permeability altogether.

Credit: https://www.sandia.gov/app/uploads/sites/275/2024/08/ClosedLoopGeothermal.png

- Closed-loop geothermal systems circulate a working fluid (like water or supercritical carbon dioxide) through sealed pipes buried in hot rock to absorb heat. Unlike engineered systems, they do not rely on natural groundwater, permeability or open fractures.

- Two main pipe designs were studied: the U-tube, which loops fluid through a horizontal section of hot rock, and the tube-in-a-tube, which sends fluid down an outer pipe and back up an inner pipe after heat exchange.

- Heat transfer efficiency depends on depth, since deeper rock is hotter, and on physical factors such as pipe diameter, fluid type, flow rate, and the rock’s ability to conduct heat.

- Supercritical CO2 can absorb more heat than water, potentially improving system performance, especially in dry rock with poor natural permeability.

- Enhanced heat transfer in wetter rock improves output, but modeling showed that even in dry rock, optimizing design, like increasing horizontal length or pipe size, can significantly improve thermal performance.

- As engineered and advanced geothermal systems move from concept to reality, several demonstration projects are testing their potential in very different settings.

- At The Bureau of Economic Geology at The University of Texas at Austin, Dr. Ken Wisian led a research team study in Presdio County, Texas to assess the feasibility of geothermal development in a remote region with hot but otherwise untapped rock.

- The remote border community sits literally at the end of electric transmission lines which makes them subject to prolonged power outages.

- The team from the Bureau showed that Presidio County does have “substantial, undeveloped geothermal resources and that Presidio would be an “excellent development target.”

- The system being developed by an Austin start-up, Exceed, uses a closed-loop system using supercritical carbon dioxide as the fluid. Supercritical carbon dioxide is a state of CO2 that occurs at high temperature and pressure, where it behaves like both a gas and a liquid. This state is more efficient for heat transfer and energy extraction, while also perhaps sequestering carbon.

- Local leaders would like to see this new and reliable energy source propel economic development in the county by providing reliable, zero carbon, baseload electricity. Excess heat from the system could also be utilized for industrial purposes such as greenhouse agriculture, food processing and refrigeration.

- The U.S. military has also worked with Dr. Wisian (a retired 2-star Air Force general) to develop geothermal power at Department of Defense facilities with several pilot projects in the works.

- EGS and AGS can allow for on-base siting which provides a secure and self-contained energy system that requires little maintenance and is very resilient.

- The baseload energy is “always on” and output can be adjusted to meet demand (aka “dispatchable”).

- If more power is needed, additional wells can be drilled, providing safe and emission-free energy.

- At The Bureau of Economic Geology at The University of Texas at Austin, Dr. Ken Wisian led a research team study in Presdio County, Texas to assess the feasibility of geothermal development in a remote region with hot but otherwise untapped rock.

Credit: https://www.nrel.gov/images/libraries/news/features/2023/20230307-full-steam-ahead-unearthing-power-geothermal-energy-graphic.jpg?sfvrsn=1fdaacf3_0

- Like any form of energy, tapping the Earth’s heat comes with trade-offs, but they can be managed with care.

- Pumping fluid deep underground can sometimes cause tiny earthquakes, though the likelihood is very low in engineered and advanced geothermal systems. Scientists monitor and adjust operations to further reduce any potential for seismic activity.

- The pipes used to drill and pump into hot rock must handle extreme heat and pressure. If the well isn’t built or sealed properly, it could crack or leak over time.

- Natural geothermal fluids are usually sourced far below drinking water sources, and EGS and AGS systems drill through and well below most any potable aquifers. Decades of experience and millions of oil and gas wells have established best practices that, when followed, make fluid migration into groundwater extremely rare. These systems are also designed to recirculate the same fluid in a closed loop to minimize risks.

- Since we can’t see miles below the surface, it’s hard to know exactly how the rock will behave. Fluids might not flow as expected or heat could escape too quickly.

- These risks are real, but engineers and scientists are working on ways to manage them safely as this technology develops.

- For decades, geothermal energy was trapped in limited corners of the Earth, but now, with the right tools, its geographic potential has expanded.

- The research being done by academic institutions like the Bureau of Economic Geology, Stanford University, The University of Utah, the Colorado School of Mines, and Cornell University, combined with support from industry and government, could make geothermal available across much of the U.S. and the world.

- With ongoing innovation and careful management of risks, engineered and advanced systems are transforming Earth’s heat into a reliable, low- or zero-emission energy source, bringing us closer to the once-distant possibility of geothermal anywhere.

Episode script

Geothermal energy, the heat of the earth, can be found under our feet everywhere on Earth.

Historically, we’ve only been able to access it in a few places, commonly in hot springs.

Much less commonly, in far fewer places, we find more intense heat, so close to the surface that it can be used to heat cities or generate electricity.

That intense heat could be developed anywhere… if we could go deep enough, cheaply enough. And that’s always been the challenge:

How to reach it, how to bring it back to the surface… and do so economically. New technology pioneered by the oil industry may be able to help.

Over the last two decades, in pursuit of oil and gas trapped in shale, drillers have perfected longer and ever more precise vertical and horizontal wellbores, at economies of scale.

Simultaneously, they’ve perfected fracturing techniques.

These may finally allow very deep, precision wells into hot rock formations, where water could be circulated to bring up the heat.

This could be done by fracturing the rock, or by running fluid through pipes.

Instead of water, some companies are testing supercritical CO2, which behaves like a fluid and could transfer heat more efficiently.

Costs for traditional drilling will remain a challenge. So other companies are experimenting with a high-powered laser to blast a deep hole.

There are many obstacles yet to overcome. But the promise of widely available geothermal energy is inspiring innovative solutions.