Credit: https://www.nps.gov/slbe/learn/nature/the-story-of-the-sand-dunes.htm

Background

Synopsis: Along the shores of Lake Michigan and Lake Superior rise the world’s largest freshwater dunes, formed by glaciers, shaped by wind, and stabilized by plants over time. These ever-changing landscapes face growing threats, but ongoing efforts aim to protect and preserve the dunes for future generations.

- Picture yourself standing atop a towering sand dune, the wind in your face and the sound of waves below. You might assume you’re near an ocean, or out in the desert Southwest. But open your eyes and you’re along the shores of Lake Michigan or Lake Superior.

- These are the world’s largest freshwater dunes, some rising more than 400 feet (122 m) high. Born from the sands of melting glaciers and built by wind, they’re still on the move today.

- Yet people build homes, trails, and roads in their path. Storms batter the shoreline. Lake levels rise and fall. Vegetation struggles to keep hold.

- These dunes are shaped by timeless forces but face modern pressures that could change them forever.

Credit: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1162512

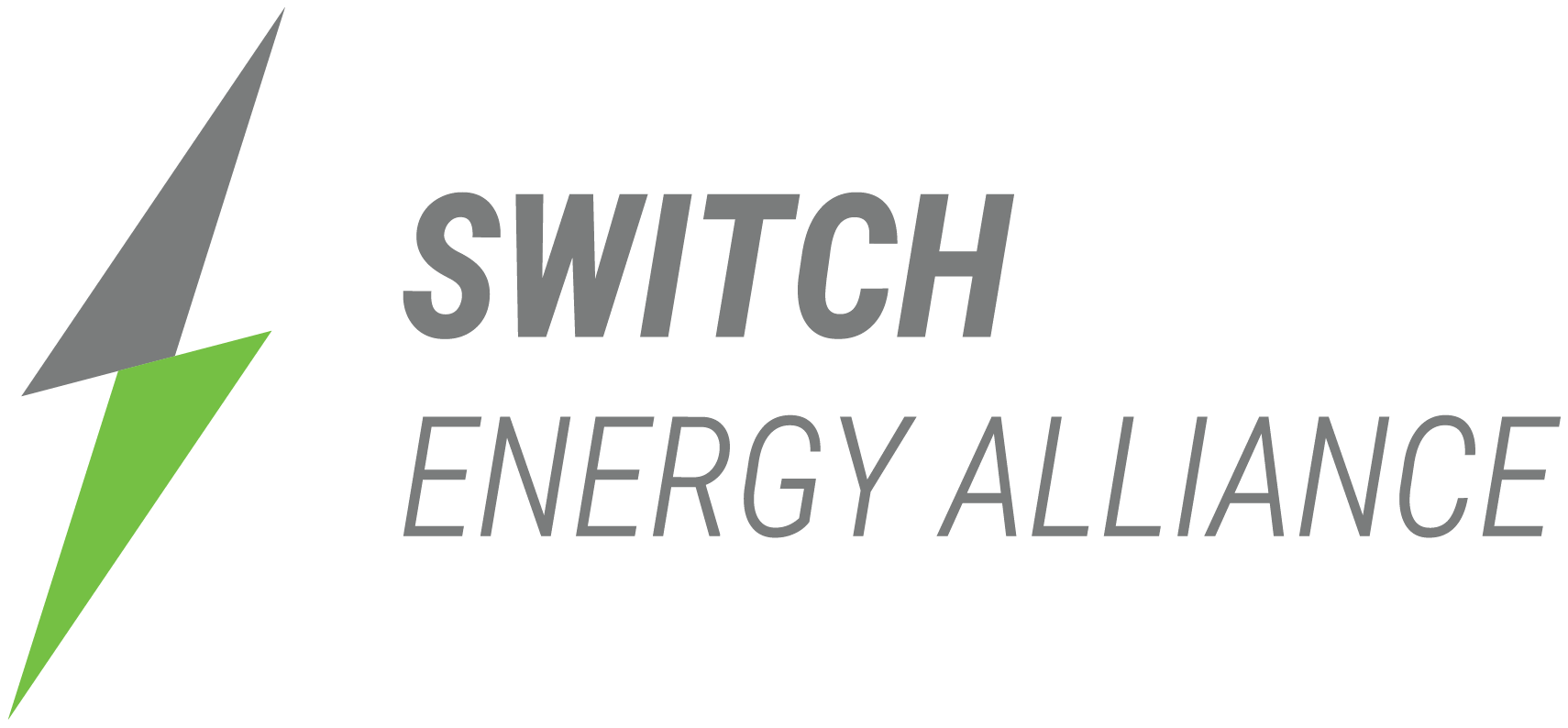

- During the most recent Ice Age, continental glaciers advanced and retreated across the Great Lakes region, reaching as far south as Illinois and Indiana, roughly 12,000 years ago.

- These glaciers carved deep basins that now hold the Great Lakes and deposited thick layers of sand, gravel, and glacial till.

- As the glaciers melted, meltwater rivers and streams carried sand into lakebeds, outwash plains, and river valleys.

- The sands that make up Michigan’s freshwater dunes originate from two major sediment sources:

- Rivers that carry glacial sediments to the Great Lakes (for example, the Grand, Muskegon, Kalamazoo, Pere Marquette Rivers)

- Coastal bluffs along the Great Lakes that are continually eroded by wind and wave action, especially on the eastern shores of Lake Michigan and southern shores of Lake Superior.

- Sand in this area is dominated by quartz that is hard, durable, and resistant to weathering. Other minerals include feldspar, magnetite, hornblende, garnet, and epidote.

- These sands are transported along the shore by waves and currents, then blown inland by prevailing westerly winds.

Credit: https://mnfi.maps.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=c701370ef9364ff18a9ea4d841fadb2f

- A dune begins when windblown sand accumulates around a small obstacle such as a plant, log, or rock, causing the wind to slow and drop its sand load.

- As more sand gathers, the small mound grows and becomes its own sand-catching feature.

- Over time, dunes can grow to enormous heights and stretch far inland.

- Most sand in dunes is carried by saltation, meaning the wind makes grains jump and bounce close to the ground instead of staying airborne.

- As wind pushes sand up on the windward (facing-the-wind) side of a dune, it creates a gentle slope. On the leeward (downwind) side, sand slips down and builds up at a steep angle, called the angle of repose, which is the steepest slope loose sand can maintain without sliding. Dry loose sand has an angle of repose of 34 degrees.

- Dunes are not fixed but gradually migrate over time. At the Dune Climb in Sleeping Bear Dunes, movement averages about 4 feet (1.2 meters) per year.

- Dune movement can bury trees, trails, and structures if not stabilized by vegetation.

- As dunes shift and grow under the influence of wind, their shape and location depend on the surrounding landscape, vegetation, and sand supply. These factors give rise to several distinct types of dunes found along the Great Lakes, each with its own formation story and defining features.

- Foredunes are low, vegetated ridges near the shore. These form during periods of low lake level but are often eroded away when lake levels rise or during storms.

- Parabolic dunes are U-shaped dunes with arms anchored by vegetation and a bare, wind-scoured interior. This type is common throughout Michigan’s Lower Peninsula along Lake Michigan.

- Perched dunes form on top of high glacial bluffs or moraines, hundreds of feet above lake level. These are created when wind reworks surface glacial material, leaving behind a thin blanket of sand. This type can be found at Sleeping Bear Dunes, Empire Bluffs, and Grand Sable Dunes.

- Dune and swale complexes are long, parallel dune ridges that alternate with low, often wet, swales. These form because of falling lake levels over thousands of years. Dunes and swales are seen in Schoolcraft County in the Upper Peninsula.

Credit: By NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory - 3615, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46926098

- While each dune type has a unique shape and origin, none would last long without help from plants. Vegetation anchors the sand in place, slows the wind, and makes long-term stability possible.

- Dune succession begins with hardy pioneer species like marram grass and cottonwood that stabilize bare sand. These are adapted to harsh, dry, unstable conditions.

- As conditions become more stable, shrubs and pines establish, creating a savanna-like landscape known as Great Lake barrens.

- Over time, the plant community transitions to a mixed forest of conifers and hardwoods and eventually mature dry-mesic forests, dominated by red oak, white pine, and sugar maple.

- In the low-lying swales, interdunal wetlands form and provide the habitat for moisture-loving flowers and grasses.

Credit: By Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore - DSC_0522, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45200069

- Though Michigan’s dunes have formed over thousands of years, their future is far less certain. These landscapes face growing pressure from both human activity and environmental change.

- Recreational damage from off-trail hiking, sandboarding, and unauthorized vehicle use can erode dune faces and vegetation. Even at protected sites like Sleeping Bear Dunes, heavy visitor traffic accelerates erosion and reshapes the landscape.

- Invasive species like spotted knapweed and Scotch pine outcompete native dune plants, disrupting the delicate succession that stabilizes the sand.

- Sand mining, though reduced in recent decades, still removes irreplaceable geological material from active and ancient dunes.

- Incompatible development such as homes, roads, and commercial structures, alters wind flow, disrupts sand movement, and can permanently degrade dune systems.

- Lake level fluctuations and stronger storms are among the most powerful natural threats to Michigan’s dunes.

- When lake levels are high, waves reach farther inland, eroding beaches and undercutting foredunes, especially during storms. Even relatively minor weather events can now flood beaches, parks, and lakeside trails.

- Lake levels are influenced by precipitation, evaporation, and river inflow. In the last decade, water levels were at near-record low but have begun to rise again. Such water-level cycles are well documented and. destabilize the dune-building process and amplify shoreline erosion.

Credit: By NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory - 3033, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46926435

- Michigan’s dunes may seem timeless, but their survival requires careful management.

- As development and recreational use increased, state leaders recognized the growing risk to the fragile landforms.

- In 1989, approximately 74,000 acres of dunes along 265 miles of coastline were formally identified as needing protection and were designated Critical Dune Areas (CDA). This law provides a balance of regulating public access and economic use with preserving ecological integrity.

- In recent years, public interest in dune protection has grown again. Conservation groups have called for stronger enforcement of existing laws and more comprehensive restoration plans.

- These efforts include removing invasive species, replanting native vegetation, and building boardwalks and designated trails to reduce erosion and habitat loss.

- Legislators have also introduced new bills aimed at clarifying development rules and expanding protections for dune systems beyond the current boundaries of the CDAs.

- Whether through stewardship, legislation, or education, these actions share a common goal: keeping Michigan’s dunes healthy and resilient.

- With the right care, these ever-changing landscapes will remain a defining feature of the region, proving that along the Great Lakes, there truly are greater dunes.

Episode script

Sand dunes are dynamic, always changing.

They occur wherever there’s sand, even thousands of miles from the sea. Even on the shores of freshwater lakes.

And the largest freshwater dunes in the world, more than 400 feet high, are in Michigan, on the shores of the Great Lakes.

They’re made of sand formed during the last Ice Age.

Continental glaciers ground up rock as they moved, and deposited sand in the basins that would become the Great Lakes.

Dunes form here, like everywhere, when wind picks up sand and carries it across the land -- until it meets an obstacle, like a rock or shrub.

That slows the wind and causes it to drop its sand, which piles up around the object.

The sand pile grows and becomes its own sand-catcher. More sand is deposited and, over centuries, a dune rises.

The Great Lakes sand dunes have been there at least that long. Though within the last few decades they’ve come under threat.

Sand mining carts them away in truckloads. New buildings block wind that could replenish them. Off-road vehicle traffic cuts some dunes nearly in half.

But state leaders, conservation groups, and volunteers have teamed up to save the dunes.

They’ve declared large areas protected. Limited mining and development. Reestablished native dune plants. Built boardwalks and trails to reduce erosion.

Together, they may be able to preserve the Great Lakes dunes for centuries, and visitors, to come.