Credit: By Fpalli - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21317012

Background

Synopsis: Chocolate is a beloved treat, but its story begins in tropical forests, dependent on volcanic soil, rainfall, and heat. From ancient cultivation to modern sustainability efforts, the path of chocolate reveals a delicate balance with the Earth.

Under the canopy of a tropical forest and in soil shaped by ancient volcanoes, a small seed takes root. It’s the start of a cacao tree, a plant whose beans will one day become the familiar and sweet chocolate. This favorite treat depends on just the right combination of earth, water, temperature, and time, yet these ingredients are becoming harder to come by.

- Humans' love of chocolate began thousands of years ago in Central and South America.

- The cacao plant was domesticated by the Olmec people, the first major civilization in Mexico, and used as a ceremonial drink nearly 2000 years ago.

- The knowledge of cacao was passed along to the Mayan population who elevated the bitter drink to a reverent status. Cacao was available to all and was a staple in Mayan households, being served with chili peppers or honey as a frothy beverage.

- The Aztecs considered cacao to be a gift from the god Quetzalcoatl and enjoyed the chocolate beverage served hot or cold in decorative vessels, often with added spices.

- The cacao beans were so valuable they were used as currency and, as a result, the upper class had more access to the treat while the lower classes treasured indulging in cacao during special ceremonies or weddings.

- The Aztec leader Montezuma II supposedly drank xocolatl (pronounced sho-co-LAH-tuhl, the Aztec name for cacao) every day, consuming gallons of the frothy liquid to boost energy and as an aphrodisiac.

- Multiple stories describe how cacao reached Europe, but most agree it was brought to the continent in the 1500s by the Spanish. Love of chocolate quickly spread with sugar and spices often added to the beverage.

- The Dutch started mixing the ground beans with alkaline salts to make it easier to dissolve in water, known today as Dutch processed cocoa powder.

- In the 19th century, the Swiss changed the world of chocolate. The Nestle brothers added dried milk powder to create milk chocolate, and Rudolf Lindt invented a machine that produced a smooth, creamy, melt-in-your-mouth confection.

Credit: By Mayan civilisation - https://www.jstor.org/stable/41780626, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9399139

- Today, chocolate is available worldwide in a variety of forms, but the rich and delicious cacao story would not exist without the abundant resources of its homeland.

- The lineage of the cacao tree can be traced to its native land in the Amazon basin in what is now Ecuador. This area still supports the greatest diversity of cacao species with each having vastly different flavor profiles.

- This region provides ideal growing conditions for the cacao tree, with humid and wet environments along with consistent warm temperatures. Differences in species exist, but, in general, temperatures of 70-90oF (21-32oC) and rainfall of 40-100 inches (100 – 250 cm) annually are needed.

- The plants thrive on the volcanic soil that is high in mineral content, providing necessary nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, calcium, sulfur, magnesium, zinc, and boron. The volcanic soil is very porous, permitting good drainage as well.

- Cacao also prefers slightly acidic soil which the volcanic soil provides with pH values as low as 5.5.

- The native cacao tree grows to a height of 12-15 feet (3.6-4.6 meters) with the extensive rainforest canopy providing just the right amount of shade needed.

- Each cacao tree flowers, and pollination must occur within 48 hours of blooming. Pollination is not done by bees but is accomplished by other insects such as ants, leafhoppers, midges, and thrips.

- Only the flowers that are pollinated are capable of moving on to the first stage of fruit production with fruit taking five to six months to reach maturity. Studies have shown that pollination rates vary from 17-40% depending on several factors.

- Each mature pod contains 20-30 almond-shaped seeds which are extracted from the white pulp, fermented, and then dried to become a cocoa bean.

Credit: By Irene Scott/AusAID, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32165990

- It is believed that cacao seeds from the Amazon basin traveled to southern Mexico both naturally by wind, water, and birds, as well as by humans via boat.

- The Olmec and Mayan civilizations began to cultivate and manipulate the species, resulting in a variety known as criolla. This version is less bitter with a floral, delicate, and fruity flavor.

- As the love of chocolate spread across the globe, so did the cacao plant. The Spanish, British, and French began growing varieties of the cacao tree in their colonies in the Caribbean and Asia. Most of this growth was dependent on the work of slaves on colonial plantations.

- The Portuguese lost control of their Brazilian colonies in the 1800s and began growing cacao on the islands off the coast of west Africa.

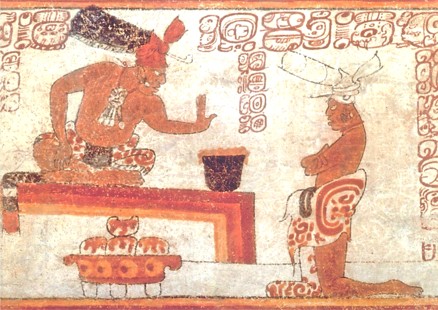

- Eventually, the commodity extended its range to the African mainland, and, today, the countries of Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire produce 70% of the global supply of cacao beans. Though not a slave economy, cacao farmers in the region still earn a paltry sum of $1 per day.

Cocoa Bean Production (in tonnes), 2008

Credit: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cocoa-bean-production?time=2008

- For centuries, cacao thrived in the humid tropics with rich volcanic soils and a shaded forest canopy. As it spread around the world, farmers worked to recreate those ideal conditions in new regions.

- But even in places where cacao once grew well, things are starting to change. Shifts in rainfall, rising temperatures, and declining soil health are making it harder to cultivate, putting growing pressure on the crop and the people that rely on it.

- Driven by El Nino events, recent years have resulted in dry and hot conditions in West Africa which have reduced cacao yields.

- In other regions where cacao is grown, above normal rainfall has caused pods to rot before harvest.

- Cacao trees are very sensitive to moisture; any changes, with either too much or too little rainfall, greatly impact crop success.

- As temperature rises, humidity is also affected, and cacao trees favor humid environments. Higher temperatures lead to higher rates of evapotranspiration, and more water leaves the plants.

- In Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire, one solution to warmer temperatures is to relocate farms to higher elevations that now have the favorable growing conditions of lower altitude regions. However, this would require disruption of natural areas to plant cacao farms.

- One plan seeks to mimic the natural rainforest conditions of the cacao habitat by leaving some trees in the area to provide shade, reducing heat and evapotranspiration. The larger trees will also protect against wind and soil erosion, and falling leaves add to soil nutrients. Planting larger trees within current farms is also being considered.

- One study that investigated the effects of rising temperatures determined that yields increased by up to 31% when measures were taken to keep cacao plants cooler by seven degrees during the hot season.

- Another method being tested to improve yield is to increase pollination. With the narrow window of pollination time and reliance on insects, using hand-pollination showed an increased yield of twenty percent.

Credit: By Willytouch - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=129938257

- Global demand for chocolate is rising, especially around holidays like Valentine’s Day, driving cacao farming deeper into tropical forests.

- In the Congo Basin, cacao production is now one of the leading causes of deforestation, clearing more forest per acre than many other crops.

- Farmers often expand into forested land to boost income, even when cacao yields are low from nutrient-poor soil.

- This deforestation releases stored carbon that threatens the role of the Congo Basin as one of Earth’s largest carbon sinks.

- Sustainable solutions such as agroforestry, which involves growing trees and crops together in the same area, and improved land management could help protect forests while still supporting cacao production.

Credit: By Everjean - https://www.flickr.com/photos/evert-jan/5509115588/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59598562

- From the minerals in volcanic soil to the warmth of tropical rains, chocolate’s journey begins with Earth’s unique resources.

- But as conditions shift and forests disappear, that balance is under threat.

- Fortunately, scientists, farmers, and conservationists are working together to protect the landscapes cacao depends on.

- With smarter practices and greater care for the land, the world’s love of chocolate can continue, rooted in sustainability and respect for the Earth that makes it possible.

Episode script

Five centuries ago, the last emperor of the Aztecs drank a full gallon each day of a coveted beverage, rich in vitamins and caffeine.

The Aztec word for it: xocolatl Chocolate.

Just like today’s chocolate drinks, his was made from the ground seeds of the cacao fruit.

The Olmecs and Mayans before him domesticated the cacao, an understory tree from Ecuador.

There and in Mexico, it thrived – under very specific conditions:

Steady warm temperatures. Abundant rainfall. Well drained volcanic soil, high in minerals.

When the cacao tree blooms, its flowers must be pollinated within 48 hours, by ants or small flies. As few as 20% of pollinated flowers produce fruit.

And those fruits hold only a handful of seeds, which must be fermented to mellow their bitter taste before they’re fit for consumption.

Mexican civilizations mixed their cacao with water, chilis, and spices. European invaders added sugar and milk to make chocolate bars.

They took the cacao to their island colonies and to Africa, where growing conditions mimicked Mesoamerica.

Today, rising heat, changing rainfall, deforestation, and overproduction jeopardize the global cacao trade.

But choco-holics don’t despair. Scientists are working with cacao farmers to develop new hybrids and sustainable farming practices to keep this sweet treat with us for centuries to come.